On average, high school wrestlers lose four to six pounds in the days leading up to a match, according to a study conducted by the American College of Sports Medicine. This cycle repeats over the course of a 10-15 week season. Wrestling, like most combat sports, groups athletes into categories based on weight. Each wrestler is weighed before every match or tournament to determine the weight class that the wrestler will compete in. Weight cutting is defined as the act of temporarily lowering one’s total body mass, often in an effort to move into a lower weight class in order to compete against weaker competition. The National Federation of State High School Associations determines the top-ends of the weight classes for the high school level, and athletes can choose to wrestle against higher weight classes.

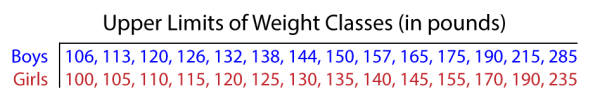

For boys, weight classes start at 106 pounds and are divided into segments of roughly eight pounds. The increments between them increase as the weight increases, ending at the highest, 285. Weight classes are more straightforward for girls: they start at 100 pounds and increase by 5 until 145. After 145, the increments between classes increase until the maximum, 235. Senior captain Jaden Perez (he/him) plans on wrestling at 150 pounds and has never failed to meet the required weight for his class before a competition.

“I’ve cut about 10 pounds this season,” Perez said. “It’s a little above average but really nothing too crazy.”

At Inglemoor and across the state, steps have been taken by the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association to ensure that weight cutting is not taken to an unhealthy extreme. At the beginning of the season each wrestler takes a urine test to measure their hydration level, and if the wrestler fails this test, they aren’t able to compete in a meet until they pass. Another test sets a baseline for wrestlers body fat percentage using calipers that measure fat at key points of the body: to the left of the belly button, the tricep and the small of the back. The WIAA sets a maximum amount of weight a wrestler can lose per season.

Brent Coburn (he/him), a physical therapist and volunteer coach for the wrestling team, said the current regulations today are different than in the 1980s, when he wrestled in high school.

“I weighed 132 and cut to 108 as a senior in high school, which is not healthy and a lot of kids were doing stuff like that, probably not to that extreme, but they saw what was happening to kids in puberty, growing,” Coburn said. “It was not a good thing.”

Weight cutting can be detrimental to an athlete’s performance and overall health. Wrestlers often cut weight through artificial dehydration, where they decrease fluid intake before their weigh-in to lose weight fast. If artificial dehydration is done before a 24 hours leading up to the match, wrestlers will likely see a drop in their stamina, according to research published by Edith Cowan University in Australia. However, senior wrestler Micheal Mulhern (he/him), said there are more effective ways to accomplish this.

“I waterload the day before, which means about a liter of water an hour I’m drinking, and then I cut it off eight hours before weighing in, and I don’t eat that day,” Mulhern said. “Between the water weight you’re going to lose and the lack of food in your stomach, you’ll usually have enough to make weight.”

Additional exercise the day before a match is another common method wrestlers use to quickly lose weight.

“Before a meet, you’ll see people running up and down the stairs in six sweatshirts trying to sweat it all out,” Mulhern said. “I know a friend who has had to run before every match just to make weight. The issue is that there’s only one varsity spot per weight class.”

The system used for determining the varsity wrestlers is unique — and highly competitive. If more than one wrestler is competing for a varsity spot in a weight class, they wrestle a match to decide who gets the varsity spot. This occurs on a meet-by-meet basis, and the number of people in a weight class shifts, so one loss does not determine the rest of the wrestler’s season. All interviewed wrestlers said that weight cutting is not enjoyable, but necessary in order to remain competitive in the sport. The pain associated with weight cutting can lead wrestlers to look for alternative methods, but these are often dangerous.

“You just have to be smart about it,” Perez said. “Don’t do any of the dumb tricks that you see on social media. There’s smart ways to do it like watching your diet instead of starving yourself and skipping meals.”

By educating parents and athletes about the dangers of certain weight cutting strategies, as well as abiding by the regulations put in place and maintained by the coach, negative impacts of weight cutting can largely be avoided.

“Most of these kids in here I feel like I can talk straight to, but if it’s something that is severe — anorexia, bulimia, maybe they’re too dedicated — they’re not going to hear you,” Coburn said. “They’re just going to keep doing what they’re doing. Sometimes you have to go to the parents and discuss that; us coaches may get together and have a discussion and decide what to do. But it’s a rare, rare case these days.”

Senior and four-year wrestler Caden Whitmire (he/him) said how his decision to cut 10 pounds over the course of last year’s season impacted both his mental health and his academic performance.

“I don’t want to say that you value your worth around [your weight], but it’s almost like that, where you’re so focused on a number that it’s impacting your academics, your relationships,” Whitmire said.

Whitmire has changed his approach to weight cutting this season, opting for a more relaxed attitude. This highlights a common misconception surrounding weight cutting in wrestling that coaches often force athletes to cut weight. At Inglemoor, Coburn and the other coaches are focused on maintaining the control that athletes have over their weight cutting experience.

“I would be very slow about [introducing weight cutting],” Coburn said. “I would almost just let them wrestle at their weight and not even talk to [a new wrestler] too much about it, because you want them to really enjoy the sport and see if it’s something for them.”

Despite the myriad risks, weight cutting is still widely practiced across high school programs. One-third of high school wrestlers nationwide have reported weight cutting practices over 10 times in a season, according to the NFSHSA. Mulhern said that at the high school level, it’s reasonable to cut weight to enter a lower class, referring to weight cutting as a “necessary evil”. For Whitmire, weight cutting is not inherently negative or positive. It all depends on the individual, and how they go about it.

“If you have weight to lose, and you can do it in a healthy way where you don’t have to skip meals or run crazy amounts to sweat out weight, it’s totally positive because you’ll go against lighter opponents, you’ll be healthier, be stronger, because you don’t have extra weight on you.” Whitmire said. “So there’s definitely positives, but you just gotta do it in a healthy way.”