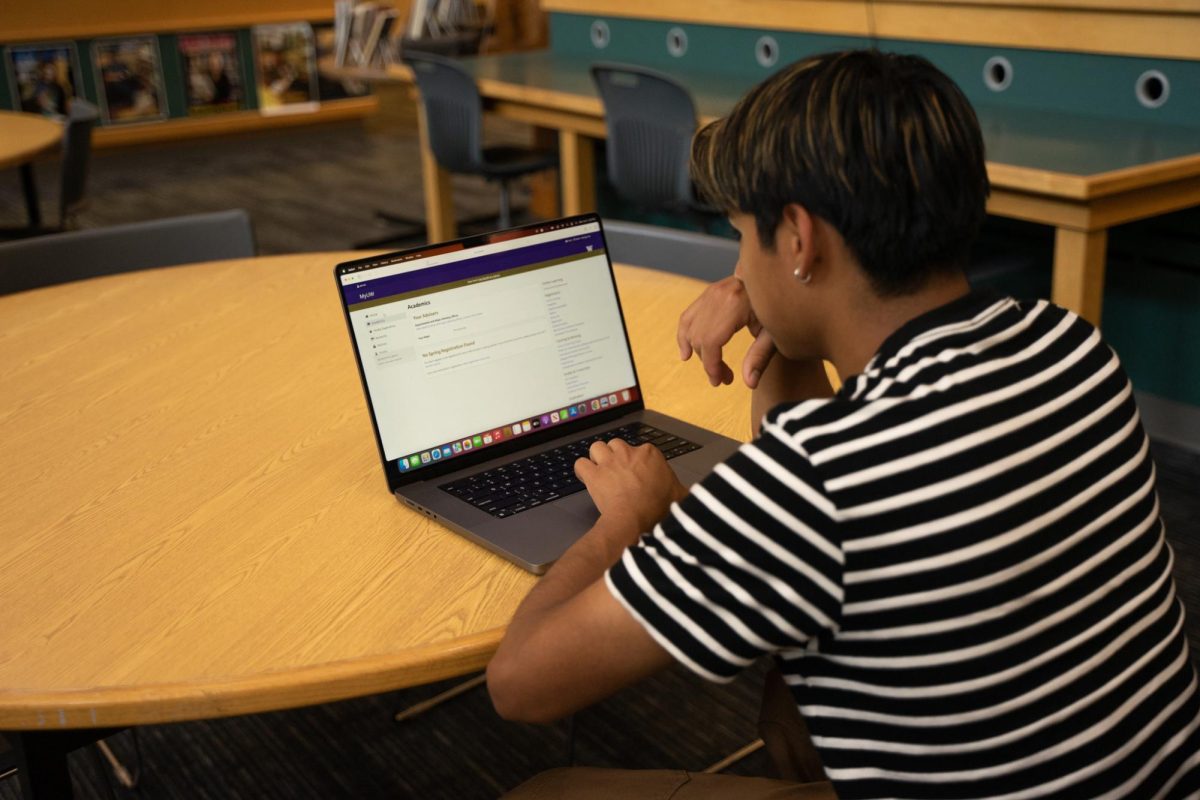

Cienne Bronson

by Aditi Jain

Adopted by caucasian parents at 15 months from China, senior Cienne Bronson has grown up with American culture her entire life. She said she struggles with discovering who she is and how it relates to being Chinese in America.

“You have two different identities: I have my American identity where that’s kind of all I know. I would kind of surprise myself in the mirror, like ‘oh my gosh. Wait, I am Chinese,’ just because I felt so American. My culture is just surrounded by western influences,” Bronson said.

She grew up in the suburbs and attended Arrowhead Elementary, in a class with only a couple of other Asian students.

“I didn’t feel represented in my school. The majority of the students [were] white,” Bronson said.

Since she was constantly immersed in western culture as a child, Bronson said she wasn’t able to learn about traditional Chinese culture and lived experiences in China.

“It made me feel less Chinese,” Bronson said. “It pointed out like ‘wow look how American I am and look how different I am, and look how much I don’t belong.’”

According to Bronson, specific details about culture, including idioms and cultural references, are very important for her to learn in order to understand her heritage. She said this was something that often became apparent in her Chinese class at school when she hadn’t known significant Asian cultural references and “felt left out.”

“Because my parents are white, they can’t pass down that knowledge, those traditional Chinese customs because they haven’t lived through that, and they don’t have that kind of experience. For me, I am missing that, because we don’t celebrate those holidays or eat Chinese food.”

She said she feels separated from both cultures: the Chinese community because she isn’t fluent in the language and the American culture because she doesn’t look American.

“In terms of my Chinese identity, I have definitely lost it, even though from the outside a lot of people can judge based on your race and appearance,” Bronson said.

Additionally, Bronson said she has been directly influenced by the stereotypes, especially one about how Asians are good at math. In seventh grade, Bronson said she signed up for the faster math track to try to fit in.

“I thought that in order to be proudly Asian, or in order to be accepted in the Asian community, I had to be smart and the way to do that was to be in advanced math.”

After dropping out after a year, she said she felt extremely embarrassed.

“And it was only like, a couple of years ago, where I finally came to terms with like, that does not define me … it shouldn’t mean anything, I shouldn’t let that affect me as much as I did. Because I felt like I had nothing to be proud about for being Asian, I felt like being good at math was something that I had to do. Math is not my greatest subject and I am fine with that because there are other ways I can embrace my culture,” Bronson said. “By no means should I be defined by some stereotype that has been built by other people.”

Robin Tan

by Minita Layal

The Khmer Rouge was the communist government that governed Cambodia in the late 1970s. It was a brutal regime that orchestrated many horrific massacres. Millions of people died or were imprisoned during the five-year rule. Thousands more were forced to flee the country in order to survive. Senior Robin Tan’s parents were among those who escaped.

His parents’ experiences play a large role in how he perceives Cambodia and his experiences visiting.

Tan said that his parents consistently feared for their lives living under the Khmer Rouge and ultimately made the decision to immigrate to the U.S.

“It was a really difficult process coming here,” Tan said. “When my dad first started immigrating here, he had to stay at a local church here and then find someone to help him through everything. It was really hard for him to learn the language, and even now he is not the best at it.”

Tan said that knowing about his parents experiences changed his view of his home country.

“I always thought that it was a decent country, but after learning about it and everything that happened, I see it as not as a safe country anymore,” Tan said.

The way Tan grew up is very different from how his parents grew up.

“It is poor and rural [in Cambodia],” Tan said. “When they were growing up, they had a hard time living and surviving there.”

Even now, he says there is a high level of crime in Cambodia; his aunt was once robbed at gunpoint.

Tan still has a lot of family in Cambodia and has visited three times.

“It was really fascinating to see where [my parents] grew up and how they lived, and to see how much things have changed. Before, when they were living there, they were living in houses built out of scrap metal and stuff. Now, they are living in actual houses,” Tan said.

He said that he enjoyed going to the temples when he last visited.

“It showed me the good side of everything,” Tan said. “It made my view of Cambodia lighten up a bit.”

Despite the very different experiences that he and his family went through, Tan still feels very connected to his heritage in part because his mother taught him Buddhist principles.

“My parents always make sure I remember my culture,” Tan said. “We do celebrate Chinese New Year and other Chinese traditions. Our religion is a really big part of everything.”

Tan’s strong connection to his heritage plays a large role in how he perceives others.

“I’ve learned to respect,” Tan said, “other people’s religions and their traditions and their views a lot more because of it.”

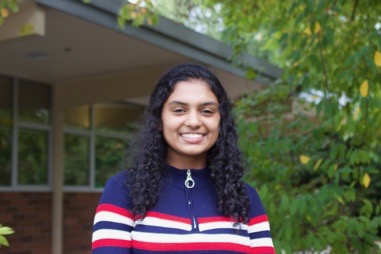

Sofia Yasinskaya

by Aditi Jain

In Ukraine, senior Sofia Yasinskaya lived in an orphanage for five years with her twin senior Katrina Yasinskaya and about 20 other children. At 14 years old, the siblings moved to America from Petrovo-Krasnosillya, Ukraine through a local organization called Otchiy Dim (Father’s House) that provides orphans with homes. They were adopted by an American family.

Sofia said the move was hard for her linguistically and culturally. She was unable to communicate well with anyone but her family, who speaks Russian, which resulted in an incident when she first moved.

“When we came here in the United States, I feel like it was even twice harder [for us] than for other people, like people with families, because we got put into a family and everything was new,” Sofia said. “I was fighting with my mom and then I decided to go for a bike ride and I got lost. I started crying and people would stop there.”

She said the people asked her if she was alright, but she couldn’t speak, because she didn’t know any English.

“They called the police because I was just there crying, and I couldn’t say anything,” she said. “It was scary.”

Sofia said she had to learn English for the first time in the span of the summer vacation that they were given before school started, which made it hard to gain relationships and adjust. She hadn’t paid attention in her English classes in Ukraine because she said she never thought she would need them.

“Sometimes, for example, I would try to say ‘wave’ and [my friend would be] like ‘what?’ and I would have to spell it out for people. It just makes things awkward,” Sofia said. “I’m really social and outgoing, but sometimes it’s hard for me. It’s like maybe holding me back because sometimes people just don’t understand.”

Additionally, Sofia also said she has trouble translating from Russian without doing a word-for-word translation. Another aspect that was confusing, according to her, was the contrast of reality from the movies. Western films, especially those portraying high school, in Ukraine had an influence on her perception of America.

“You know how in movies, because in Ukraine, we got assigned seats, but here, I thought oh my gosh, in US, there are no assigned seats,” Sofia said, “but then there were, which was a problem.”