High school curriculums are designed so that students can take courses that will prepare them for a successful future. As students leave the comfort of their classrooms and enter the professional world, they are offered a wide variety of career options, some of which are considered STEM: science, technology, engineering and math.

According to various studies and statistics, there is a lack of female representation in these fields, both in and out of the classroom. A cause of this imbalance may be gender stereotypes.

“I think there’s a lot of stereotypes; they don’t necessarily mean to push [girls] away from STEM fields but they just subconsciously do,” junior Hallie Wall said.

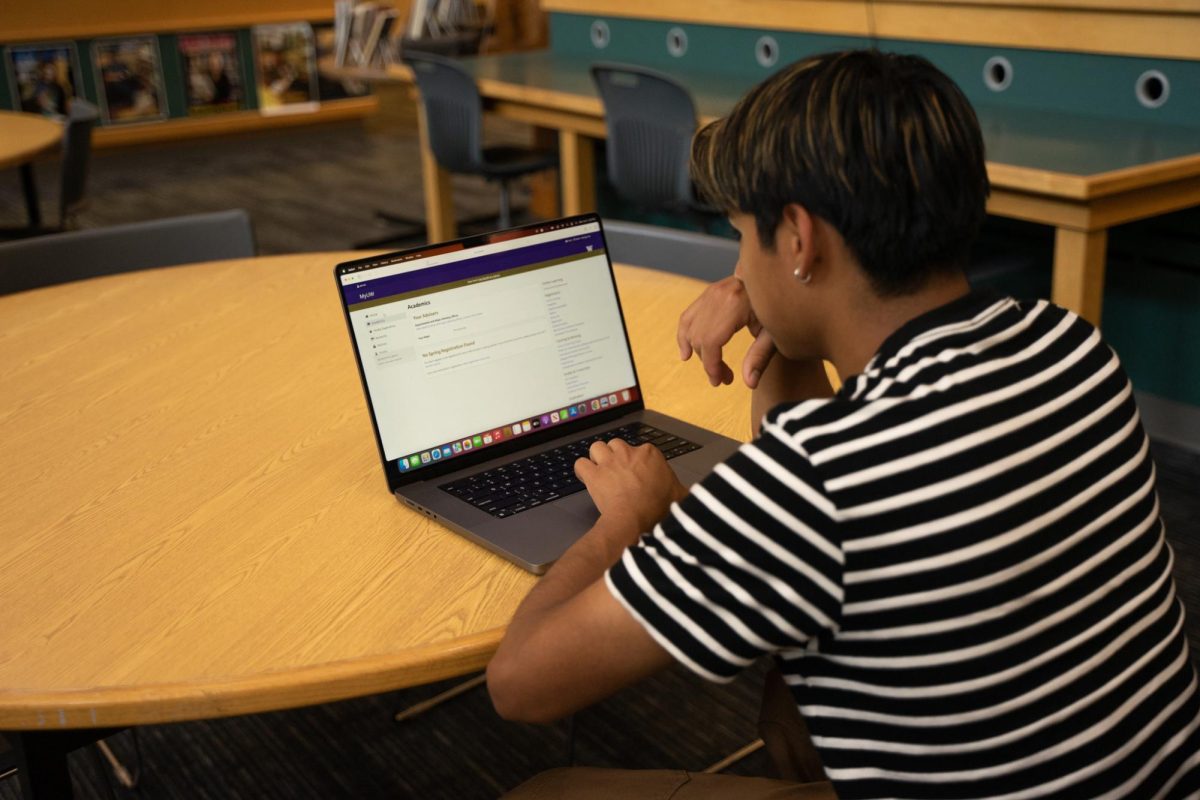

This may not always be the case. Sophomore Ethan Stone said that when students are required to take certain classes such as math or prerequisites for other courses, there is a relatively equal balance between the number of boys and girls. But according to Stone, when students have more freedom to select the courses that best fit with them — which generally occurs during junior year — the situation changes.

“From what I’ve heard, I think there is a bit of gender imbalance with biology having more girls and physics having more guys,” Stone said.

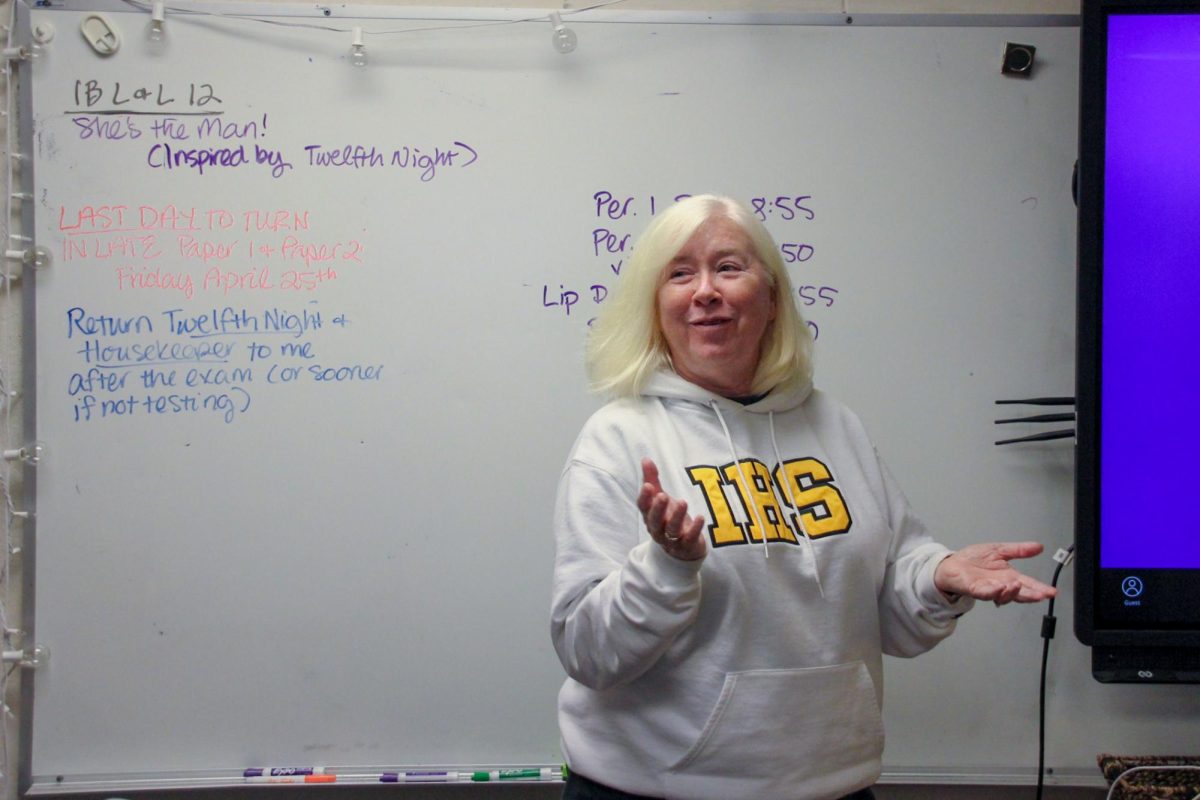

Last year during course registration, junior Katie Anderson noticed this gender imbalance; she saw that when IB program students were choosing their science classes, there was a distinct gender gap. Although she ended up going on the physics route, Anderson said this imbalance is likely a result of the stereotype that males often dominate the maths and sciences.

“It seems to be that women are better at relational aspects of things and men tend to be more clinical and analytical. So that could be a reason why they tend to excel in math-based and science-based things and women tend to excel in English and writing-based things,” Anderson said.

Over the years, stereotypes such as these affect the career paths that female students will eventually choose. As as a result of this, junior Ryan Brownell said that it’s less socially acceptable for girls to go into STEM fields, particularly those related to engineering and math.

“When I think of a mechanic, I usually think of a man. It’s purely wrong, [but] there’s just this male ideology that goes with being a mechanic and engineering is kind of part of that whole idea,” Brownell said.

On the other hand, junior Johnson Kuang said he believes that the societal expectation of boys being better at math and science has never applied to his computer science class.

“Honestly, it’s about who works harder, it’s not about any preconceived stereotypes. In the end, we found that the girls that were in the class did better than most guys because they worked harder at it,” Kuang said.

Similarly, Wall said that conventional image of there being less women involved in STEM is motivating her rather than hindering her.

“Having that stereotype of guys are better at it is encouraging me because I’m the kind of person that if I get told I can’t do it, then I have to prove them wrong,” Wall said.

Anderson said that with all of this heightened awareness about girls in STEM, it’s still important to recognize that one’s interest in the subject should always rule over the improvement of gender-based statistics.

“I feel like people should go into a field they’re genuinely passionate about, not just because we need to fill a gender gap,” Anderson said.

Although it’s questionable as to whether or not the gender gap in STEM fields will ever completely close, sophomore Ingrid Bautista said there is no doubt that it has improved significantly in recent years.

“You hear how usually [STEM] is male-dominant and whenever there’s a female breakthrough, it’s pretty big,” Bautista said. “Being a female, it’s empowering and inspirational. It shows I can be so much more.”