What is Passover?

On the 14th day of the Jewish month Nissan — which includes the weeks of March 25 to April 25 on the Gregorian calendar — Jewish families around the world celebrate the eight-day-long holiday of Passover. Also known in Hebrew as Pesach, Passover commemorates the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt.

In the Torah, the Hebrew scripture, it is written that centuries ago, Egyptian pharaohs enslaved the Jewish people for 400 years. To free them, God sent the Hebrew prophet Moses to speak to the pharaoh and demand the release of the Israelites. When the pharaoh refused, God sent 10 plagues upon Egypt. After each plague, Moses would return to the pharaoh and repeatedly demand that he “let my people go.” The pharaoh continued to refuse until the release of the tenth and final plague: the death of the firstborn in every Egyptian household. Before this plague, God instructed the Israelites to slaughter a lamb and mark their doorposts with its blood, ensuring that the angel of death would pass over the homes with this sign, sparing their firstborn. The pharaoh finally succumbed to Moses’s demands and let the Israelites go. However, the pharaoh was known to change his mind, so the Israelites fled Egypt in haste and did not have time to let their bread rise, resulting in the creation of matzah, a type of unleavened bread.

The Book of Exodus, the second book of the Torah, tells the initial story of the Israelites’ freedom from Egypt and introduces the Jewish laws and traditions that followed. There are four rules during Passover. The first is to not eat, possess or benefit from any leavened food. The second is to eat matzah as a replacement for all leavened foods. The third is to celebrate with a Seder, a meal to commemorate the story of Exodus, and the fourth is to refrain from working on the first and last days of the holiday, as well as the Sabbath. During the week-long celebration, the Exodus’s Passover story is retold and celebrated by these rules as a remembrance of the hardships that Jewish families endured.

Traditionally, to begin the week of fasting from all leavened foods, the Seder is held on one of the first two nights of Passover. At the Seder, family and friends gather to honor the story of their enslaved ancestors. They read from the Haggadah, a foundational Jewish text that sets forth the order of the Passover Seder. Reading the Haggadah at the Seder table is believed to fulfill the mitzvah, which roughly translates to “good deed,” of every Jew to teach the Egyptian Exodus story to their children.

The Seder follows 15 steps and typically begins with the Kadesh, or the recitation of the blessing of the Kiddush over a glass of wine or grape juice. This is followed by Urchatz, a spiritual cleansing from pouring water three times on each hand. The next steps revolve around the Seder plate placed at the center of the table, which is composed of seven symbolic foods that represent different parts of the Israelites’ history. The first bite of food from the Seder plate is the karpas, a green vegetable dipped in salt water, symbolizing both spring and renewal as well as the tears of the enslaved Israelites. The matzah is then broken into three pieces before the longest of the 15 Seder steps: the Maggid. During the Maggid, families retell the story behind Passover while the youngest child at the table asks the traditional four questions included in every Haggadah. All four questions revolve around the basic question of “Why is this night different from all other nights?”

The ritual continues with a second hand washing, but this time it is accompanied by a blessing. The next few steps are a series of eating different foods that each represent a part of the Passover story until the final step, the Hallel. This is the final Seder ritual, which includes singing special songs of praise to God, and then filling, blessing and drinking the fourth cup of wine. The Seder is not only a core religious observance of Jewish faith and identity, but also a time to connect with others and bond over a shared history.

‘Our differences make us strong’: Eric Levine on the evolution of his Jewish faith

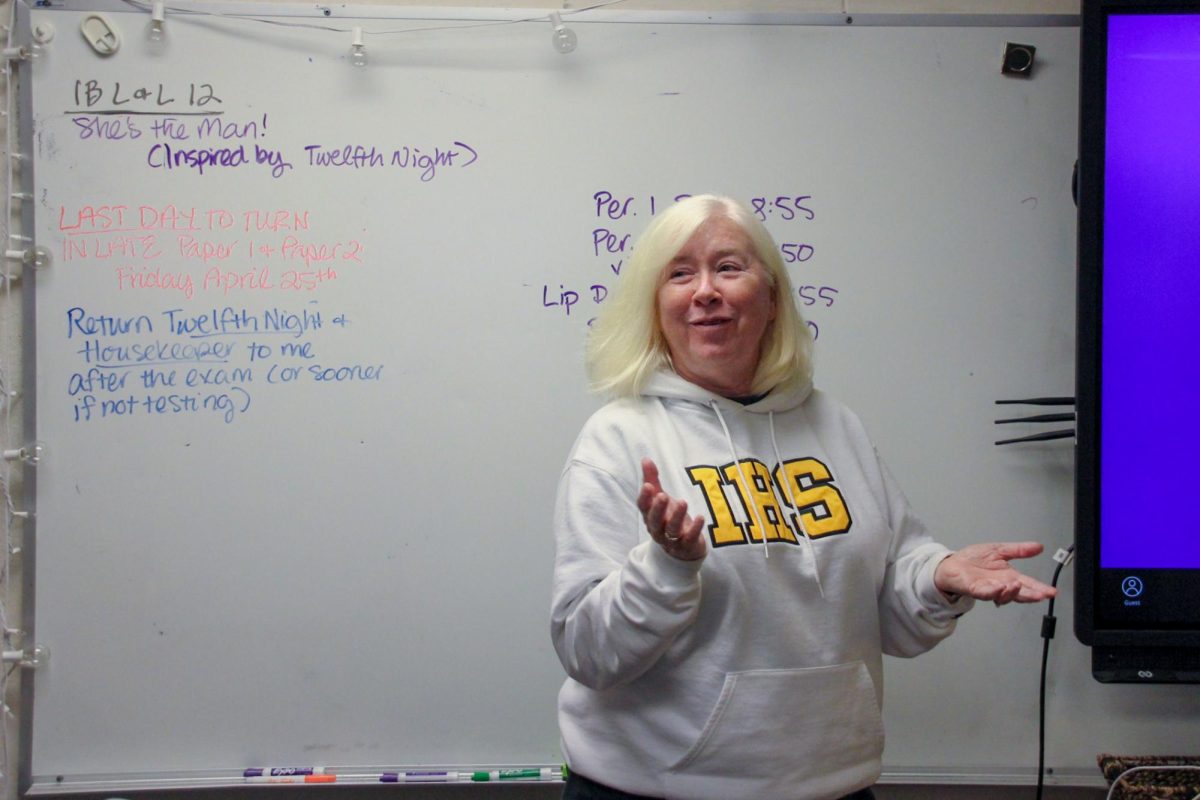

Physical Education and Sports Medicine teacher Eric Levine (he/him) practiced Judaism until the end of college and grew up celebrating a variety of Jewish holidays. Up until his college years, Levine regularly celebrated Passover with his family and friends. He said that the holiday gave him a sense of community and was one of the holidays that his Jewish household fully celebrated.

“My family actually hosted the Seder at our house. Usually between 30 and 40 or so people — lots of families and kids from our synagogue. Sometimes we also invited close friends as well to experience it,” Levine said. “We went through the Haggadah, which is the book that takes you through the story of Passover, the questions and talked about the plagues, taking us to the meal at the end.”

After regularly practicing Judaism for a large portion of his childhood, his college friends introduced him to the Birthright Israel Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps young adults of Jewish descent visit Israel free of cost. Levine said that the organization introduced a new way to define his faith in Judaism. Visiting Israel led him to identify more as a spiritual Jew rather than a practicing one.

“Our understanding out here in Tacoma, Washington was, ‘Oh man, in Israel it must be so religious and everything.’ And then we’re there, and everybody’s like, ‘Yeah, no, that’s just your Americanized idea of how things were here. It’s not like that,’” Levine said. “Yes, there are some more religious, more by-the-book orthodox Jews that live that way. But they said, ‘We live here and we experience it every day. We feel Judaism in everything that we do. We don’t necessarily need to practice it all the time to prove that we are Jewish, so to speak.’”

This realization began to shape most of Levine’s beliefs around Judaism. After marrying his wife, who grew up practicing Catholicism but has since abstained, he said that his perspective on religion shifted. To him, religion became less of a constricting lifestyle and more of a spiritual one.

“She really made me think about what religion was to me — like you hear something from your parents or your community leaders or your religious leaders and think this is the way that it is. That’s how it was for me. And she was like, ‘Why do you believe that?’ Well, that’s all I was ever told. So why would I believe anything else?” Levine said. “I’m not saying don’t follow your beliefs and your family beliefs, or your community beliefs or anything like that. But when my wife started asking me questions, not to change my mind about things, but just to ask, ‘Are these really things that you believe? Or is it just because it’s what you’ve been taught?’ It really opened my eyes.”

As a father of two, Levine said he and his wife prioritize raising their children through the values of both Jewish and Catholic practices, rather than focusing on the rules and principles of religion itself. He said that he wants to teach his kids about the morals of what Judaism has taught him, rather than the set of rules from the Torah. For Levine, Judaism is more about building community, family and becoming a good person.

“A lot of what we raise them to be encompasses a lot of religion from the Catholic perspective and from the Jewish perspective, just without Shabbat services and things that I experienced,” he said. “Just being a good person, respecting others, accepting who they are, no matter what they look like or how they dress or what their religion is, or their beliefs. Our differences actually are what makes us really strong.”