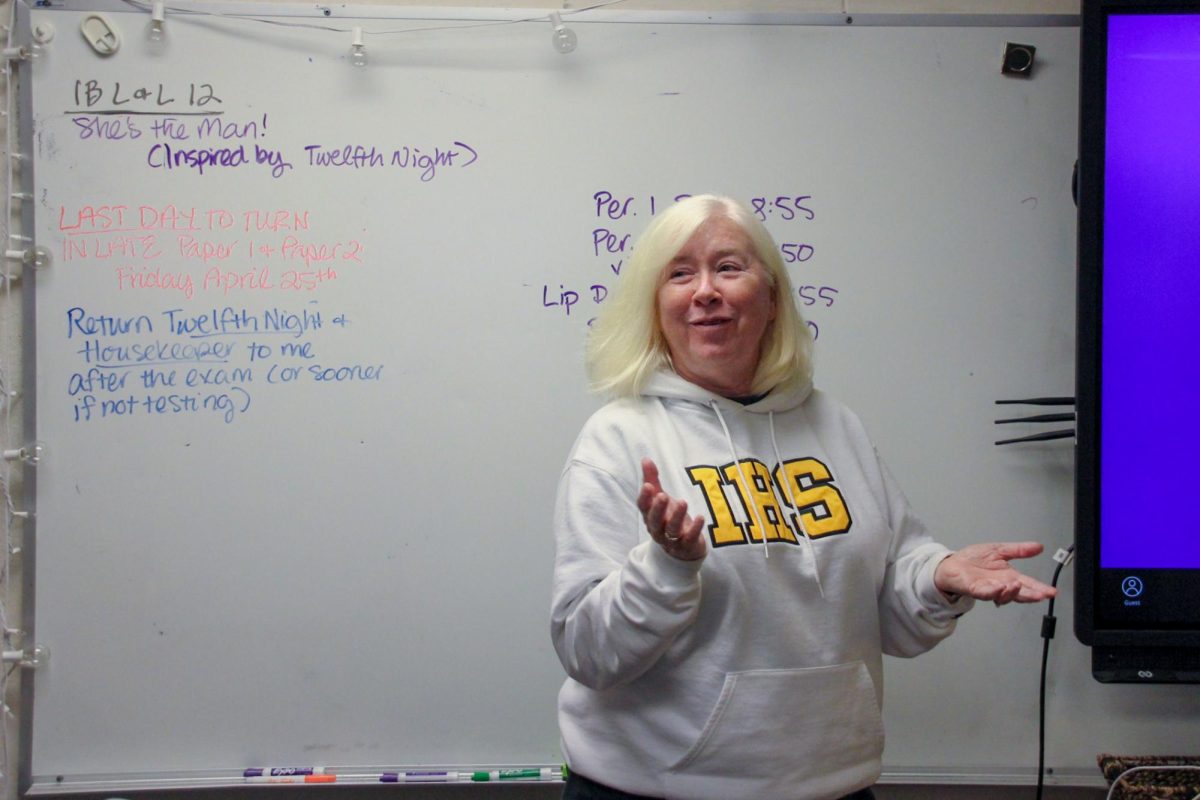

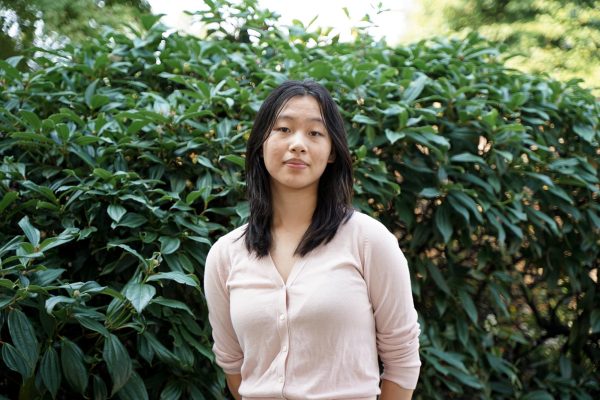

Hired in 2023, assistant principal Dr. Ebonisha Washington (she/her) brought the goals of increasing student engagement and drawing the community closer. Washington said her identity as a queer Black woman has engendered both challenges and new opportunities for connection with students.

“My very last year in my doctoral program, what I realized is it’s not about a title. It’s about making these connections with the kids and the parents and the staff in a way that’s meaningful and lasting. So if I left, I have shifted the culture, and so that is my goal,” Washington said. “I don’t need to move and be a principal. I don’t need to move to central office. I just want to work on building culture that makes everybody feel like if I walk by you, you know that I care about you. That’s the feeling that I want for the entire school community.”

Describing herself as always very reserved and introverted, Washington entered her administrator training program at the encouragement of a previous coworker who told her that she could change a room with her voice. Although she still gets nervous when speaking to large crowds, that program convinced her to move into leadership.

“When I got into my admin program and started seeing (that) what was needed in education was literally people just saying, ‘I’m going to put my heart on the table and give everything to these kids that I can,’” Washington said. “This is not about ‘I need every student to go to college.’ This is about helping kids fulfill their dreams. That’s it. That’s what I’m here for.”

Before she attended college, Washington said she did not have any teachers of color. She described her motivation for a career in education to be, in large part, an attempt to heal the kid that she was. In secondary school, for example, Washington was an honors student in the gifted program, which she said no one expected from her.

“I went to high school in California in very white spaces, and I think that when you are in those environments as a young person, you also take on some of those identities. So it’s not that I thought I was white, but white kids were free with their queerness. They didn’t feel like they had to hide it. They didn’t. So I started taking that on, like when I was a teenager. I was 16, it was junior prom, and the school that I went to never had same sex couples go to a prom together, and there was a girl that I was really cool with, Melissa, and she was also queer, and she’s like, ‘We’re going together, and who cares? And we’re gonna act like we’re a couple.’ We weren’t a couple — we’re just friends. But it was an attempt to disrupt the idea of queerness back then. This was 1995.”

“I think that I would have loved for somebody to set the bar high for me,” Washington said. “When I was growing up — when you were a student of color — there was an expectation that you would do one of two things: you would either drop out of school or you would play sports.”

It was only due to her family’s insistence that she got the rigor she deserved, Washington said. If she could go back in time, she said she would want a stronger support system from her teachers. Now, she wants the experience for kids of color to be different from what she had.

“I always have higher expectations of kids,” Washington said. “All of the kids deserve for somebody to believe that they can achieve anything that they want to.”

Now, in her administrative duties, she believes that representation is important, and she tries to be visible on campus to contribute to that representation.

“I think that for a good portion of students of color, they will come to me and also girls will come to me if they are assigned a different administrator because I am a woman, and they feel more comfortable,” Washington said. “So I use that to my advantage, and it’s helped build relationships with students where I don’t know that students of color typically see an administrator as anything other than a disciplinary.”

“I went to high school in California in very white spaces, and I think that when you are in those environments as a young person, you also take on some of those identities. So it’s not that I thought I was white, but white kids were free with their queerness. They didn’t feel like they had to hide it. They didn’t. So I started taking that on, like when I was a teenager. I was 16, it was junior prom, and the school that I went to never had same sex couples go to a prom together, and there was a girl that I was really cool with, Melissa, and she was also queer, and she’s like, ‘We’re going together, and who cares? And we’re gonna act like we’re a couple.’ We weren’t a couple — we’re just friends. But it was an attempt to disrupt the idea of queerness back then. This was 1995.”

“I went to high school in California in very white spaces, and I think that when you are in those environments as a young person, you also take on some of those identities. So it’s not that I thought I was white, but white kids were free with their queerness. They didn’t feel like they had to hide it. They didn’t. So I started taking that on, like when I was a teenager. I was 16, it was junior prom, and the school that I went to never had same sex couples go to a prom together, and there was a girl that I was really cool with, Melissa, and she was also queer, and she’s like, ‘We’re going together, and who cares? And we’re gonna act like we’re a couple.’ We weren’t a couple — we’re just friends. But it was an attempt to disrupt the idea of queerness back then. This was 1995.”

Her racial and gender identity is always at the front of her mind, Washington said, because she must consider how other people view her. She said she thinks of herself as Black first, and then a woman, because people tend to identify her by her race first.

“As a person of color, just thinking all of the time, ‘How do people see me?’ So I need to make sure that I’m smiling or I’m not too aggressive in what I’m saying, even though I’m confident in what I’m saying,” Washington said. “So, I second guess myself a lot.”

Still, Washington struggles with negative self-talk and some anxiety when asserting herself. Part of that battle originates from stereotypes like the “angry Black woman,” she said.

“I feel like I’m unapologetically myself. I’m Black, I’m queer and I’m a woman. I’m all of the things and then — deal with it, right? But I’m also really quiet, and I don’t speak unless it’s intentional and it’s needed in that moment. And so I would say that the biggest challenge has been to come outside of the things that are going on in my head,” Washington said. “Like, ‘Don’t say anything. Don’t be confrontational, because they’ll see you this way because of these things about who you are.’”

None of these aspects of her identity will change, Washington said, so she no longer cares what other people may think or say about them.

“I think that it’s challenging when it’s with students — obviously, right?” Washington said. “Because people are still homophobic, transphobic, all of the phobics, and we have students who are not all the way ‘out.’ And so what I try to do is just support that. And so who I am is a direct reflection for students, is like it’s okay, but it’s also okay to stay where you are if you’re not ready. And so I try to stand up in that everyday, and it’s because I just don’t think that anybody deserves to be mistreated based on an identity.”