Life is full of messes, but some can make you reconsider your career.

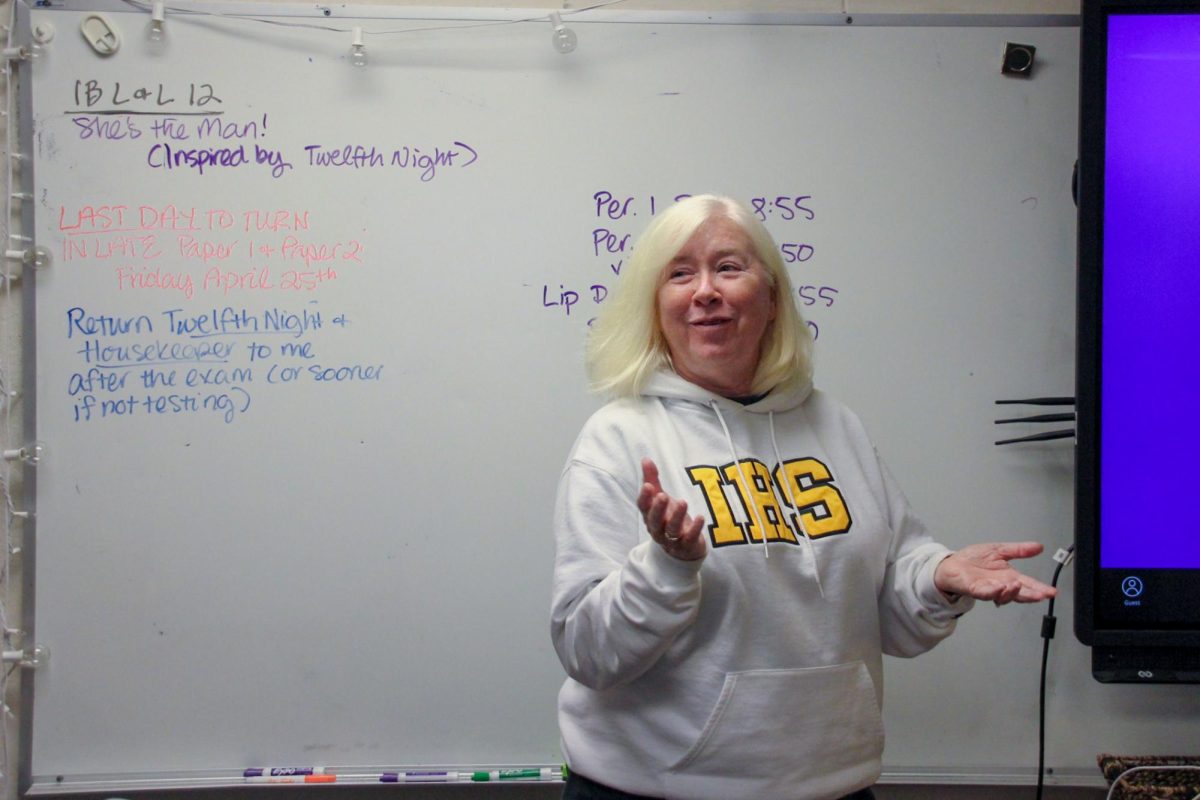

On a work day like any other, faculty manager Sophia Jennings (she/her) received an urgent work order.

“They called me: ‘Sophia, can you please come to clean the carpet in 104?’”

Jennings said that she had no idea what she was walking into. An accident had left a mess so unbearable that Jennings, a custodian of over a decade, picked up her phone and half-jokingly told her boss, “I’m quitting!” Yet, in the face of that breaking point, she stayed, scrubbed and set off to where else she was needed.

This incident occurred 10 years ago, and Jennings has now been working as a custodian for 22 years. She began her career working the night shift from 4:30 p.m. to midnight. With the halls emptied of students and teachers, it was just her and a handful of other custodians sweeping away the day’s footprints.

“It’s like you’re alone,” Jennings said. “Now, in the morning, I have more responsibilities, because a teacher can call me if they have an accident in that room, or the lights break.”

A custodian’s job goes far beyond household cleaning. They learn to fix light fixtures, to deep-clean carpets and tiles and to chemically clean various surfaces.

Custodian Alicia Cervantes (she/her) arrives for her night shift just after the last bell rings. She tidies up the classrooms, gymnasium and bathrooms before leaving around midnight.

“The last thing I have to do is security. I make sure that every door is locked. If not, I lock it and the windows I make sure is closed,” Cervantes said.

Even when the team faces absences due to days off or sick call-ins, the to-do list does not get any shorter. Those on-duty still make sure to prioritize cleanliness.

“We do the — we call it trash and run — which is just basically, to save as much time you do the basics — bathrooms and trash. Vacuuming can wait for the next day, but bathrooms have to be disinfected every single day,” night-time custodian Brian Vazquez (he/him) said.

As a recent recruit, Vazquez experienced the demanding work of a substitute custodian. Before custodians are hired for a permanent shift, they spend their hours covering for co-workers who call in sick or are otherwise absent.

“It was kind of hard because as a substitute, you can be working a whole three days of just morning, and then the next day they’ll change it to a night shift, so you’ll be leaving work at midnight, and then the next morning, at five or four in the morning, they’re like, ‘Hey, we need you to open up,’” Vazquez said. “That change of sleep schedule is kind of messed up.”

While their regular shifts are eight hours long from Monday to Friday, the custodian’s most enjoyable yet toughest work of the year goes unseen. Once the school is void of activity in the summer, all seven custodians deep clean every inch of the campus. Compared to the regular, mutually exclusive shifts, the summer’s extensive work is relieved by a ‘united front.’

“It’s always fun when there’s no students because there’s other stuff we do. There’s rooms where, to change the filters we crawl around the vents upstairs, and it’s fun,” Vazquez said. “We share fun stories. Sometimes we can put together music.”

Once students and staff flood back to school, the campus comes back to life. Jennings said that she especially appreciates the social aspect of her job, both talking to the students and working with the other staff.

“I’m lucky because my administration — the principal and everything — they are really nice with us,” Jennings said. “I like students; I mean, it’s fun. When they notice, they say, ‘Oh, thank you.’”

Small words of gratitude and appreciation go a long way towards making the job rewarding, but not all interactions reflect that same respect. Jennings said that in her experience, custodial work in other environments like malls or hotels offers little respite, low pay and short vacations.

“We feel like some people, they said to us, like, we are here,” Jennings said, motioning toward the ground with her hand. “But you know, everybody’s cleaning their house. The difference here is that they pay us.”

There is much to uncover beneath the surface of custodial work. Vazquez said that custodians are perceived differently by those who know their story. He said that many custodians use the pay to save for college or a car. Some also suffer injuries that prevent them from taking another career path.

“A lot of people degrade the job a lot,” Vasquez said. “Custodial work is one of the jobs that people think, ‘Oh, you clean toilets for a living.’ And I get it. I completely understand why no one wants to do it, but if you get to meet the people — there’s very smart people.”

In many ways, being one of the few school custodians fosters a close community. For Vazquez, his co-workers keep him going without exception.

“I don’t want to let them down, because it’s hard when someone calls out sick,” he said. “It encourages me to just keep coming and helping out.”

Whether it be through sweeping through long nights at school or responding to unexpected incidents throughout the day, Jennings said that she has undoubtedly developed a connection with the school environment that stretches beyond work.

“The school, to me it is like my second house — sometimes maybe my first house because sometimes I spend more time here than my house. So I don’t understand, like so many students, they trash the school. I mean, would you like to come to a nice, clean school or come to an ugly school?” Jennings said. “It’s something I wish they can see.”