On Nov. 4, a seven-week union workers’ strike at Boeing ended with a contract offer to raise machinists’ salaries by 38% over the next four years, provide greater contributions to employees’ 401(k) retirement plans and pay a $12,000 bonus to striking employees for accepting the offer. Despite the failed return of pension plans — a key goal for striking employees — 59% of the union members voted in favor of Boeing’s third contract offer, officially ending the strike. Boeing said it will take several weeks after Nov. 12 — the last day for workers to return to the production line — to fully resume building passenger planes.

Boeing is still dealing with issues after the strike’s conclusion, which cost them $11.5 billion in losses. They have had to continue cutting costs and the workforce. On Nov. 13, Boeing confirmed plans to lay off 17,000

employees, equivalent to 10% of its workforce. Employees who were laid off received 60-day-in-advance notices the same day.

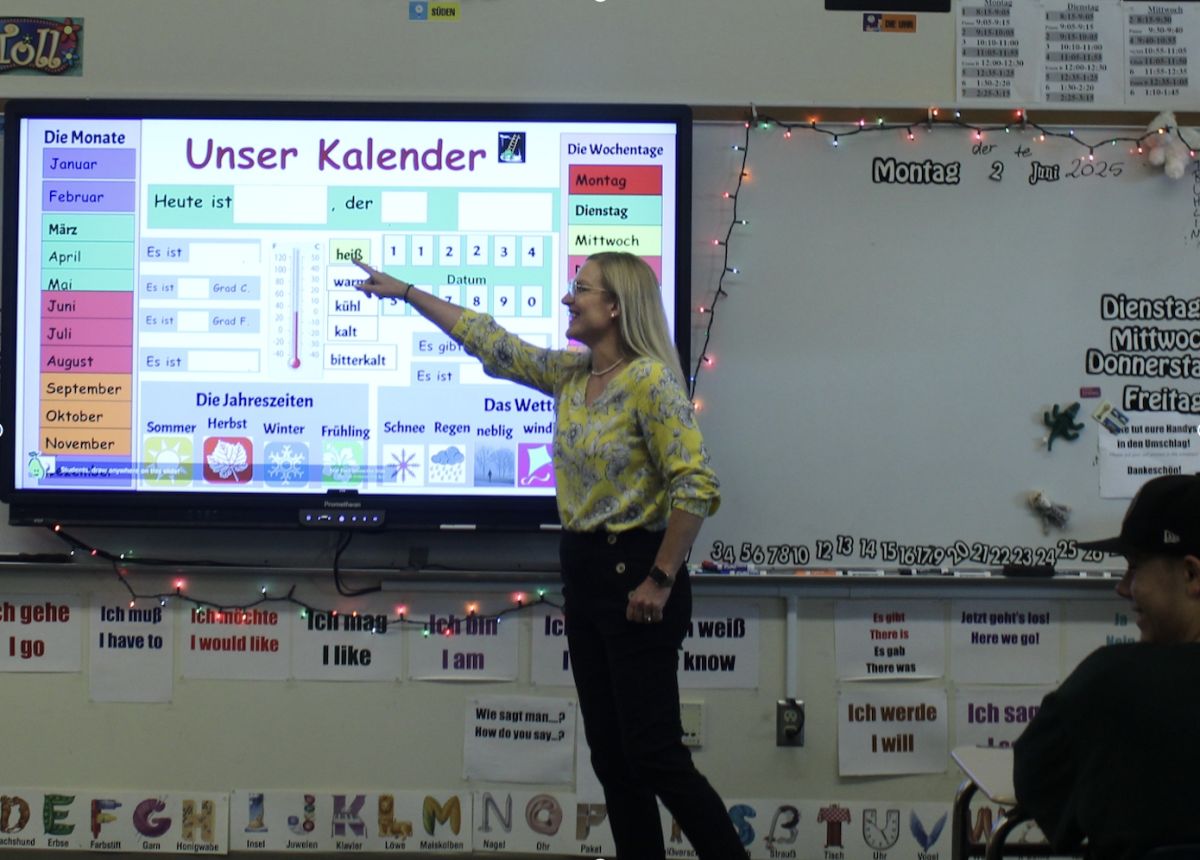

“Not only were workers not feeling like they were benefiting in the past couple of years, but I know that morale at Boeing was a company-wide problem,” social studies teacher and IB coordinator Amy Monaghan (she/her) said.

In Washington alone, Boeing employs over 65,000 people. As one of America’s top exporters of airplane-related products, the company is a major source of opportunity for students interested in engineering and aerospace, so the effects of the strike go beyond the company.

“We have students whose families relocate to this area because of Boeing, so it’s right in our own backyard,” Monaghan said.

On Sept. 13, 33,000 union workers began striking after a long period of dissatisfaction and a 94.6% vote rejecting Boeing’s first proposal to increase wages by 25%, as the offer did not meet the union demands of a 40% wage increase. Workers have also expressed frustration over Boeing’s refusal to reinstate its pension program, which was discontinued in 2014. The union workers’ strike was the first in 16 years and spanned Washington, Oregon and California.

Before the strike, Boeing was facing a significant financial decline. The company’s third-quarter financial report from July to September reveals an operating loss of over $5 million. In contrast, losses for the same quarter a year before were under $1 million, marking a significant decrease in revenue. The door plug blowouts and plane crashes in 2018 and 2019 raised more safety concerns. Boeing is also nearly $58 billion in debt and has faced even greater financial repercussions since the strike.

On Oct. 19, Boeing proposed a second contract to the workers, which included a 35% wage increase over four years and a one-time payment to machine workers’ retirement plans. However, it still fell short of the union’s demands, resulting in a 64% majority vote to reject the contract. This extended the five-week strike and disrupted Boeing’s supply chain. A critical supplier of Boeing’s aircraft components, Spirit AeroSystems, was forced to temporarily suspend employees who build parts for Boeing 767s and 777s for three weeks due to economic strain and a work shortage. On Nov. 12, Spirit AeroSystems confirmed they would receive $350 million in funding from Boeing to compensate for the losses from the last four years.

With their production rates down, especially those of their best-selling 737s, the company’s stock price fell to a record low on Nov. 12, but the conclusion of the strike may change this.

“There’s a lot of demand for new airplanes,” Monaghan said. “And the company is already way behind in its ability to fill orders, so from the company’s perspective, they want to get everybody back to work.”

Monaghan said that while the end of the strike poses several issues, there’s still a bright side.

“When workers go back to work, these contracts are signed on both sides. That’s always a positive. It’s a way of moving forward – it’s a sign of some stability.”