The trend of “grade inflation” — the distribution of grades that don’t align with the student’s mastery of taught material — has prompted debate over the degree to which grading alone should be used as judgment of student performance. A 2022 report from ACT Inc., a nonprofit dedicated to helping students achieve education and career readiness, found that the average high school GPA increased from 3.17 in 2010 to 3.36 in 2021, with the greatest grade inflation occurring between 2018 and 2021. However, average ACT scores have stayed the same. As a result, schools have started reassessing recent policies, such as the late work and grade floor policies.

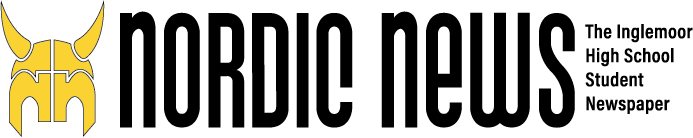

During the COVID-19 pandemic, NSD implemented a 50% minimum grading floor for students, which was later lowered to 40% in 2022. Before the pandemic, this grading floor didn’t exist, and students who scored between 0-59% received a failing grade. The Shared Decision-Making Leadership Team called for a vote for teachers to decide whether or not they wanted to remove the 40% floor; those eligible to vote are members of NSD’s teacher’s union, the Northshore Education Association.

Pre-IB World History II and IB History of the Americas teacher Luke Derror (he/him) said that the purpose of the 40% floor was to support students who had trouble completing homework and assignments.

“It made it easier for students who had missed a lot of school or had some type of issue where they couldn’t complete homework to have a pathway to graduate,” Derror said. “Before, if you missed enough assignments, you couldn’t dig yourself out because you were at a 0%. But if you’re at a 40% or 50%, then it’s a lot easier to dig yourself out of a hole.”

Despite the good intentions of the grading floor policy, Derror said students who can complete their assignments on time have taken advantage of it.

“I saw the amount of students who passed the class go up, but then you run the risk of it going the other way, and you’re passing students who have done three, five assignments for the whole semester out of maybe 100 assignments,” Derror said. “Is it right to give them a passing grade?”

Junior Kat Boiko (any pronouns) said the 40% grade floor completely changed her study habits and the amount of effort they put into school. Boiko took their first high school course in sixth grade, and they said they initially put in much more effort.

“And then we went online, and a lot of grade inflation policies came into play, and all of a sudden, the effort was at zero,” Boiko said. “I flunked my way through middle school until I got to high school, and then I started trying again, but my GPA has been a little bit screwed up.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, NSD also implemented numerous late work policies that allowed students to retain full credit after the due date had passed. In the 2021-22 school year, teachers were contractually obligated to give students full credit for late assignments up to one week before the end of the semester. In the 2022-23 school year, the policy changed to require only one week of leniency for full credit. Last year, the grace period was reduced to just one day. After teachers brought concerns to the NEA, it was proposed that contractual late policies be removed. This motion passed on Sept. 23.

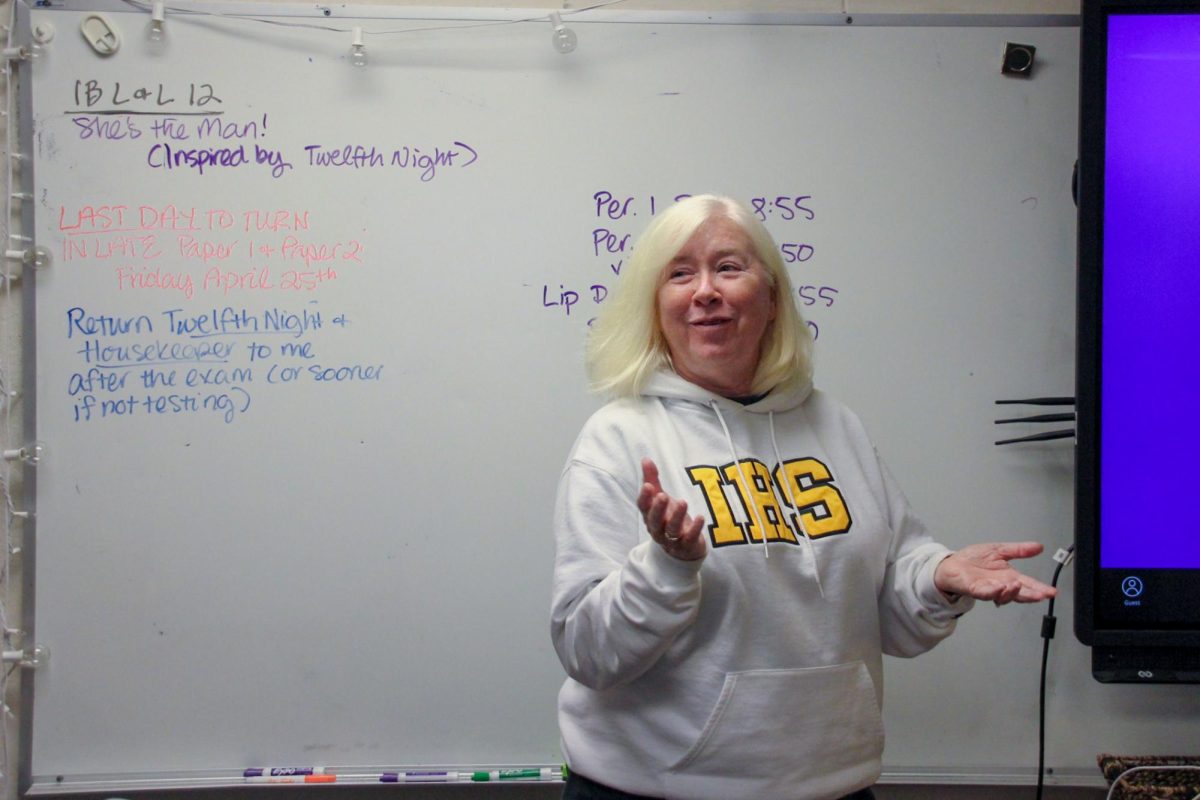

“When we were doing the 50% floor and accepting work really late for full credit, that was really frustrating, because people weren’t motivated to get it done,” IB math teacher Sally Anderson (she/her) said. “They would come up to you two months in and try to hand you work that was for two or three months ago, and you had to take it, and you had to give them full credit. That’s really not helpful.”

Pre-IB History teacher Kelly Gregory (she/her) said that in her classes, late work contributing to grade inflation is less of an issue because the courses are discussion-heavy. If her students don’t thoroughly prepare for the discussions, they aren’t able to fully engage, therefore earning them a lower grade.

“There’s sort of a natural consequence to not being prepared. I think that reflects out in the real world as well, right?” Gregory said. “If you haven’t done the prep work, then you’re not ready for a meeting. You’re not ready for a sales pitch, whatever it is. And so I think it shows up in my classroom in that way.”

Gregory said that although letter grading doesn’t apply to real-world work standards, school grading systems give students a framework upon which to build good habits. Students develop work ethic, integrity and perseverance by adhering to deadlines and taking their grades seriously. In contrast, the change of grading systems to be more accommodating to students can be damaging.

“My job as a teacher is less focused on the grades and more focused on teaching responsibility and accountability,” Gregory said. “Those are skills that once you are outside of the classroom are going to support you in the workplace, in higher education, wherever you’re headed outside of this. If you can’t get something turned in on time, then that’s problematic.”