As of Oct. 13, there have been 841 fentanyl overdose deaths in King County this year, according to the Medical Examiner’s Office. Already exceeding 2022’s total of 712 deaths from fentanyl overdoses, the drug is responsible for more than 70% of the 107,000-plus fatal drug overdoses in the United States this past year. Currently, fentanyl overdoses are the leading cause of death for Americans aged 18-45.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid used to treat patients with chronic severe pain or end-of-life cancers. It is safe when used under the supervision of medical professionals, but is deadly when illicitly produced and mixed with other drugs. Fifty times more potent than heroin, just 2 milligrams of fentanyl — equivalent to a few grains of salt — is considered a lethal dose by the Drug Enforcement Administration. According to the DEA, a single kilogram of the drug has the potential to kill 500,000 people.

Fentanyl is illicitly manufactured primarily in China, Mexico and India, then exported to the U.S. in the form of powder. Due to its extreme potency, it’s easier to smuggle: a small bag of fentanyl powder yields the same profit margin as a kilogram brick of heroin or cocaine. Fentanyl is being pressed into counterfeit pills to mimic legitimate prescription opioids or mixed in with other illicit drugs, often containing lethal doses. The DEA found that nearly half of the counterfeit pills tested contained a lethal dose of fentanyl, with some containing more than twice the lethal dose.

Fentanyl is also highly addictive, and individuals can quickly develop a tolerance, causing them to take higher doses to catch the same high. This results in drug dealers and cartels making stronger pills, causing even more users to overdose. Regular opioid use can also cause opioid use disorder, which means individuals are physically dependent on opioids, having brain changes that affect their thinking, priorities and relationships. David Baure (he/him), the training manager with Seattle & King County’s Overdose Prevention and Response Program, said that for some, the switch to fentanyl wasn’t a voluntary choice.

“It’s important to remember that some people who use opioids — or those who have an opioid use disorder — may not have been attempting to use fentanyl as a substitute but rather some have found that they are no longer able to get other opioids and that the drug supply changed,” Baure said. “Strong opioids, especially after long-term use, can be highly addictive, and people can become rapidly addicted to Fentanyl though they were not trying to be.”

However, public health officials have been taking preventative steps through harm reduction programs. Alison Newman (she/her), a Program Operations Specialist at the University of Washington’s Addictions, Drug and Alcohol Institute, said that these harm reduction programs distribute safe use supplies.

“They distribute clean syringes, safer smoking supplies and a lot of naloxone and fentanyl test strips as well,” Newman said. “They’re also really trying to get people who are interested, access to the medications either buprenorphine or methadone, which help reduce someone’s risk of dying by overdose by half and help treat opioid use disorder by reducing craving and withdrawal. They’re trying to help get wraparound services to people who use fentanyl and need housing or employment support as well.”

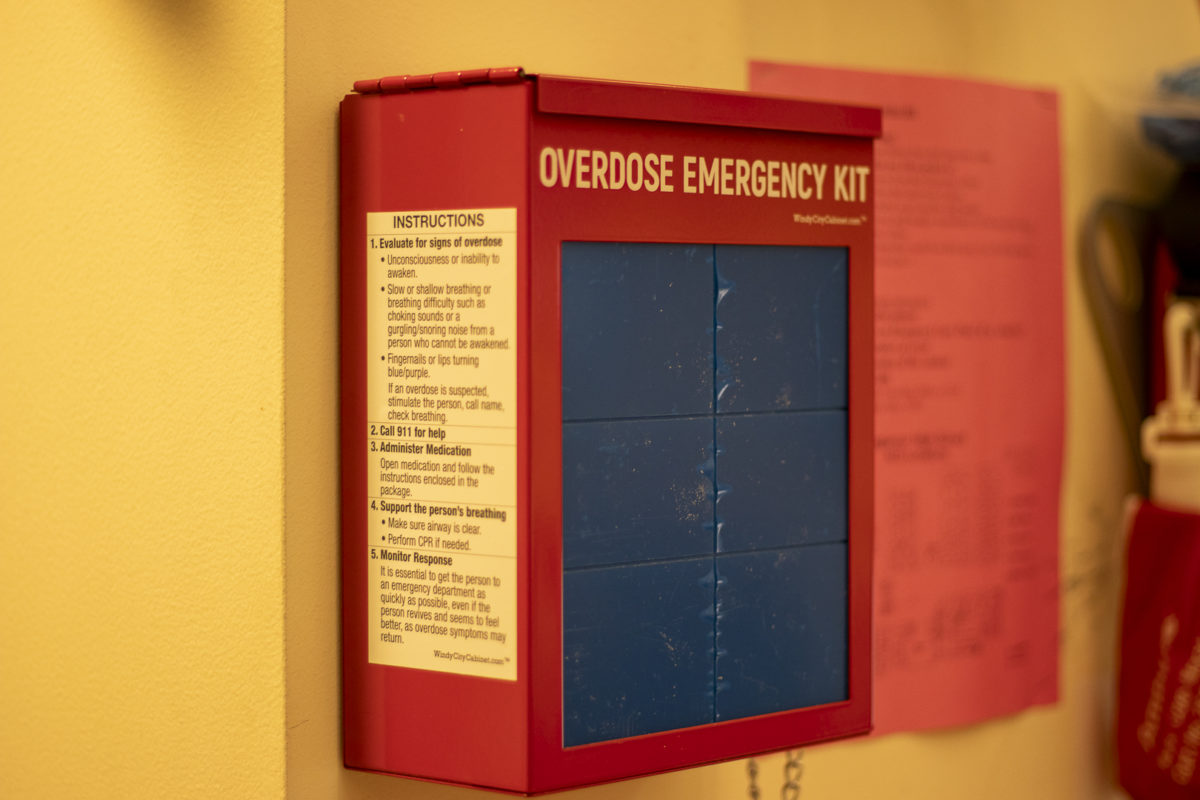

Naloxone, offered through harm reduction programs, is known by the brand name Narcan. It is a nonprescription drug that rapidly reverses the effects of opioid overdose, and it recently became available over-the-counter and is free for Washington state residents. King County residents should order Nalaxone from Kelly-Ross Pharmacy either online or onsite at the Polyclinic, and all other residents can order Nalaxone via mail from the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance.

“Naloxone is pretty amazing and lasts about 30 to 90 minutes, which might hopefully allow someone to get medical care,” Newman said. “Anyone in the state of Washington can have and carry naloxone and use it in case of an opioid overdose, and there’s no age limit for it.”

Fentanyl strips are cheap, fast and easy-to-use paper strips that test drugs for fentanyl. They can be ordered online for free from King County or picked up from vending machines located at Peer Seattle and Peer Kent.

“They don’t tell you how much is in [the drug], but just knowing if there’s fentanyl present or not can help people make a choice about how to use more safely and try and reduce their risk for overdose,” Newman said.

The Washington Department of Health plans to purchase 75,000 fentanyl strips this fiscal year and distribute them to syringe service program partners. Furthermore, Washington state’s settlement with the nation’s three largest opioid distributors — McKesson Corp., Cardinal Health Inc. and AmerisourceBergen Drug — requires the state to spend $476 million of the total $518 million won from the settlement addressing the opioid crisis. The money would also be spent on substance abuse treatment and expanding access to overdose-reversal drugs and providing housing, employment and other services for those struggling with addiction. From that settlement, King County expects to receive $1 million to $1.5 million per year for 17 years.

Mental health is one of the biggest underlying problems responsible for drug overdose deaths. In 2015, more than two million U.S. adults had an opioid use disorder, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Of that two million, 62% of them had a co-occurring mental illness. Mental illness, which often goes undiagnosed, increases the risk for opioid use disorder and can interfere with a person’s ability to make healthcare decisions. Patients with a diagnosed mental health condition are more likely to get opioid prescriptions despite their greater risk of addiction and overdose.

“Think about why somebody might start to use drugs in the first place,” said Jason Williams (he/him), a research scientist at the Addictions, Drug and Alcohol Institute at the University of Washington. “Those underlying causes — depression, mental illness, back pain, despondency, despair — there are all these things that we as a society don’t do a good job at, that drive people towards finding something that can do a good job at dealing with it. We all have ways of coping with things, and some of those coping mechanisms are more healthy than others.”

Washington has numerous measures to mitigate and treat the effects of opioid addiction and overdose. Washington’s Good Samaritan Overdose Law protects overdose victims as well as individuals seeking medical assistance for the victim from drug possession charges. There are 37 Opioid Treatment Programs located throughout Washington that provide counseling and medical services for those experiencing opioid use disorder. Websites such as lacedandlethal.com and stopoverdose.org offer additional information on fentanyl-laced substances, crisis lines and treatment resources. Click here to find opioid treatment programs in Washington.

“Another thing to know is that opioid use disorder is treatable; people do recover,” Newman said. “If people are interested in finding options for treatment, the Washington Recovery Help Line [1-866-789-1511] is a really great resource. And for young people, I think a really important message is to assume fentanyl is in any drug that you didn’t get from a pharmacy, and either choose not to use it or if you do use it, use around other people and make sure someone has naloxone.”