Depression is an illness that can be just as debilitating as any other, but it isn’t always perceived that way. While we unquestioningly sympathize with those who physically suffer, the public perception of emotional disorders like depression can prevent the same kind of sympathy; we just don’t view the mind the same way we view the body.

Mental disorders can be stigmatized more often and more easily than those of the body. Though we’ve made progress to legitimize disorders like depression, there still isn’t the same level of acceptance for those with mental illness. The stigma surrounding these disorders can prevent proper care for those in need, and perhaps make their conditions worse.

About 350 million people worldwide suffer from depression, and though there effective treatment exists for those who need it, fewer than half actually receive treatment. This is thought to be due, at least in part, to the stigma surrounding such disorders.

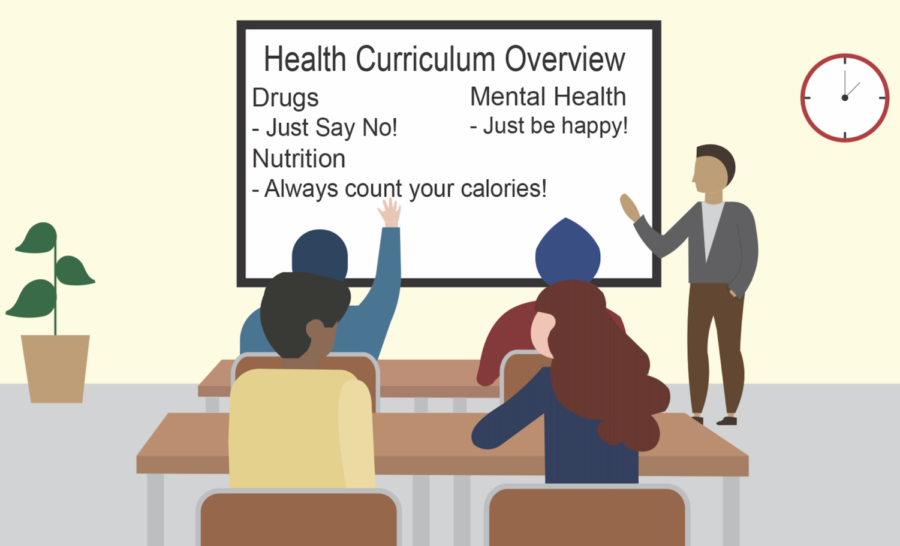

It can be easy to develop such stigmas when two aspects of health—the physical and the mental—are seen as separate.

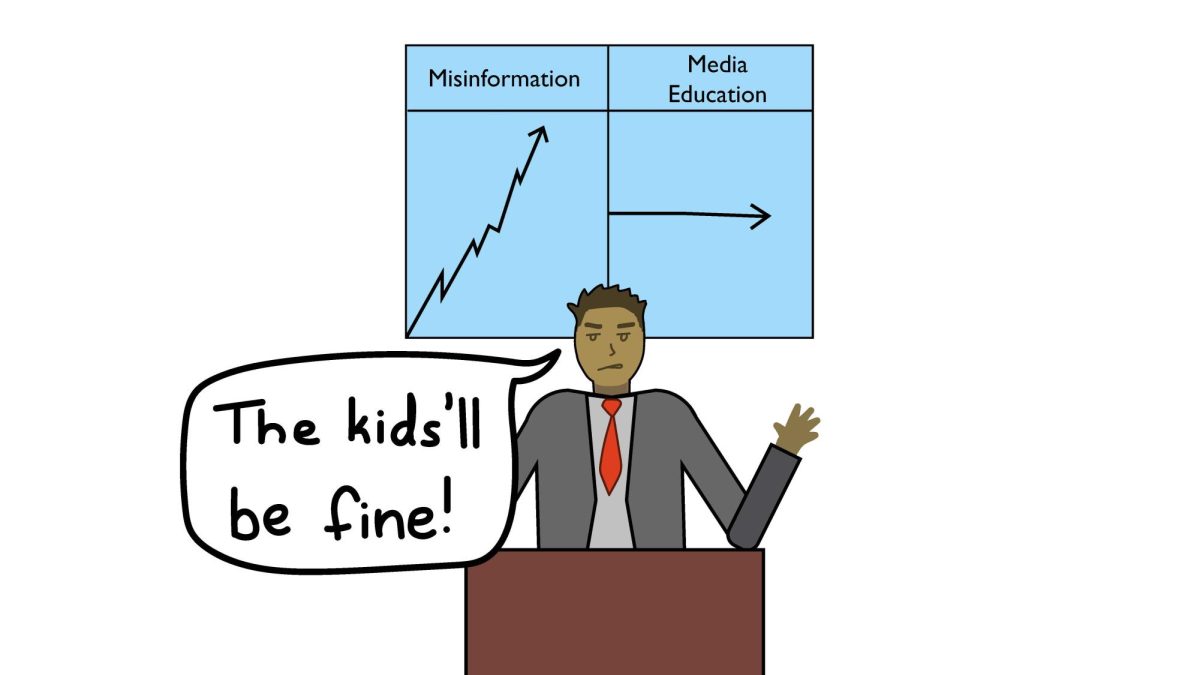

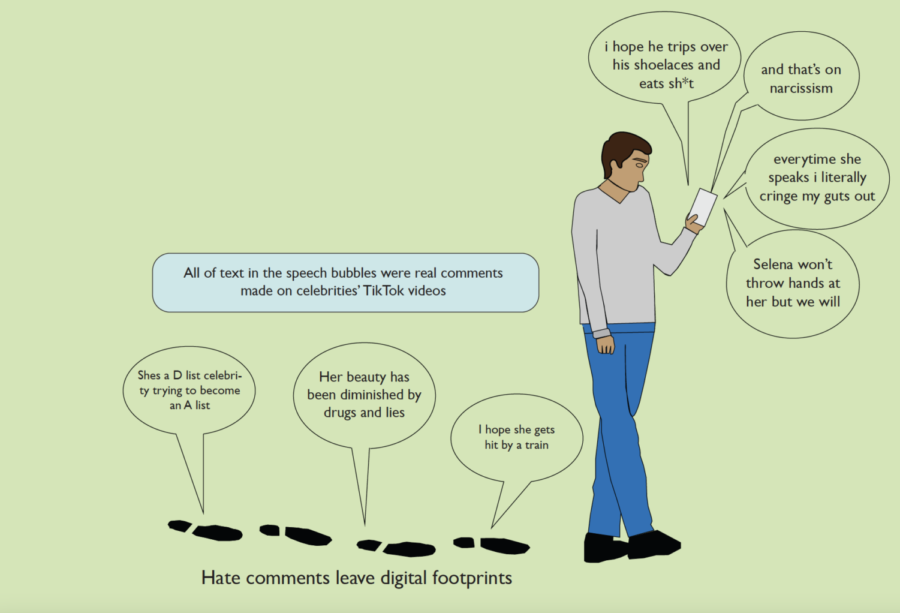

In a society where we nurse wounds while ridiculing tears, it’s easy to adopt a perceived dichotomy between the body and the mind. Children are barraged with media that advocate simply adopting a positive attitude, as if one’s emotional state were his or her choice. No inspirational poster would suggest anything like “Just don’t have a paper cut anymore,” and yet, we seem to accept the equivalent of this regarding depressive states.

We’ve certainly improved in liberalizing our view of neurological disorders—most of us know about hormones and neurotransmitters that can alter our moods—but there still pervades this back-of-the-head notion that those who experience depression, anxiety or other emotional disorders are somehow weak-minded. This not only limits access to treatment, but it could also prevent depressives from ever even pursuing it.

To dispel this stigma from our culture, we have to view the mind in the same way we view the body. Like all of our functions, our emotions serve specific purposes.

From simple impulses to the most complex emotional states, all of our sensations work to serve us and to keep us alive. Hunger will compel us to eat, and fatigue will make us want to rest. These, which comprise the “lizard” or “reptilian” brain, are our most inate compulsions, but the higher brain functions are only more complex, and not inherently different, from these.

Happiness basically works as a way to catalog beneficial environments and behaviors, while sadness records those that may be detrimental to our health. When there is a bias in this record keeping, depression or mania can occur.

The brain is an organ, and it functions and malfunctions in the same ways that other organs can.

This may be an unfamiliar way to think about our feelings. It may seem to minimize the marvel of the human brain. We don’t tend to think of our emotional states in the same way we think of our digestive systems, but perhaps that’s how we need to think.

It’s difficult to let go of this, our final marker of superioriy to the rest of nature. To allow the most intimate components of ourselves—our emotions—to be manipulated with medicine and therapy would be to hold ourselves to the same cognitive level as animals.

This desire to separate ourselves from the rest of the natural world is a human one—we crave validation, and this can lead us to draw conceptual lines that frame ourselves as superior—but it’s a desire that tends to hinder social progress. Ask yourself, “Isn’t it more animalistic to deny comfort to those who suffer, regardless of the form their suffering may take?”