Paddle past ignorance: acknowledging stolen land

The first people of the Salish Sea have lived along the lakes, rivers and saltwater for more than 10,000 years. Before pioneers arrived, the Coast Salish people lived in winter houses called longhouses. Longhouses were made out of cedar logs, and each house had a name and a headman. They were usually between 60 to 80 feet long and could house hundreds of people. If there was a powerful house, then the other houses in the area also used the name of this strong house, said Michael Evans (Waq́usqidəb) (he/him), the Chair of the Snohomish Tribe of Indians.

“The people on Lake Washington were called the Lake people. The people over by Juanita were called the Willow people, and they were associated with the larger, stronger group called the Inside People. The word for Inside People is Duwa, meaning Duwamish,” Evans said.

Evans said that the lands near what is Kenmore today were managed by either Duwamish or Snohomish families. However, in 1855, Washington territorial governor Issac Stevens, Chief Seattle and representatives of Duwamish and Snohomish descent signed the Treaty of Point Elliott. The treaty ceded millions of acres of land to the federal government in exchange for protected reservations. Stevens proposed putting the first peoples of Washington on seven reservations.

“Most of the people that used to live in these longhouses were decimated because of diseases,” Evans said. “And then with all the wars and other things going on, a lot of the people left the area. There was not a lot left; they were put in concentration camps called reservations, or they were put in boarding schools, and only about 10% of people came out of that. Most of the people that went died eventually.”

Only 0.2% of Kenmore’s population of 23,478 listed their race as American Indian or Alaskan Native in the 2022 census. Suzanne Greathouse (she/her), the President of the Kenmore Heritage Society, said the history of indigenous people and their relationship with the land often involves violence, displacement and exploitation.

“My ancestor chose to marry a pioneer instead, and was protected by the white man,” Evans said. “The white male marrying the native female and because of that a lot of those people survived, because they had that protection. But those that lived on the reservation didn’t, and whatever it was they did allow, it was almost all taken away, including their lives.”

Land acknowledgments are formal statements that recognize the theft of land from indigenous peoples and the colonization, genocide, forced relocation and ethnic cleansing they faced. Evans said land acknowledgments are an important first step, but a small one.

NSD’s Racial and Educational Justice Board created a land and peoples acknowledgment that is presented at school events like graduation and non-spirit focused assemblies.

“I think it’s important to recognize colonialism, because not only does it help us give a little perspective and context to the places we’re in and the history behind it, but also the horrible actions that happened because of colonialism,” Principal Adam Desautels (he/him) said.

Greathouse said KHS goes beyond land acknowledgment by educating Kenmore residents about indigenous history and partnering with various local tribes to teach children about native languages and plants. Although KHS doesn’t engage at the tribal government level, they have worked with people from federally and non-federally recognized tribes in community-based projects.

Federally recognized tribes can apply for government funding for services and programs. Criteria required to become federally recognized include parameters on Indian entity identification, political influence or authority, governing documents, proof of descent, unique membership and congressional termination. The Snohomish Tribe of Indians’ petition for federal recognition was denied in 1983. Currently, the Duwamish tribe is also not federally recognized.

“Those that had reservations were recognized, and they had all the treaty rights. And so the Snohomish Tribe of Indians had to go back to the federal government and prove that they needed to be recognized by the federal government. And it has never happened,” Evans said.

Federally recognized tribes operate as domestic, independent nations and are treated at the same level as the state government. Tribes can also be recognized by the state, which means they do not receive the same benefits as federally recognized tribes but are acknowledged for their historical and cultural contributions.

Tribes can ask the government for environmental statements: documents that outline the environmental impacts of proposed projects, and anything else that affects their treaty rights.

“Every drop of water affects the grass, it affects the critters and animals that are on the land. It affects the ability to hunt and fish in traditional ways so yes, [first people] should have some say in those things,” Evans said.

The Muckleshoot tribe controls the waterways around Kenmore. Greathouse said anytime the city of Kenmore wants to do something with the water, they have to contact the Muckleshoot tribe and a variety of other governmental agencies.

“We were trying to get the city of Kenmore to meet with the governing body of the Tulalip,” Greathouse said. “But they couldn’t wrap their heads around that; they didn’t see them as a government agency, which I think is part of the challenge. I think people have a lot of misconceptions about how they’re organized.”

The federal government recognizes 574 tribes, 29 of which are in Washington. More than 200 tribes do not have federal recognition.

“Those who are not federally recognized, they have no money, they have no reservations, they have no resources, and they are being called names,” Evans said. “And what we would like to do is be recognized, and the first step is land acknowledgment.”

Parts of Native American history are taught in every American history class at Inglemoor, but the information included varies by teacher and by year. In 2015, Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction required schools to teach the histories of Washington’s federally recognized tribes and provided an OSPI-created curriculum. However, data from the Office of Native Education showed that in 2021, 115 or 40% of Washington school districts did not have teachers who’d completed the required training. So far, local tribes have mostly paid for the teacher training and curriculum.

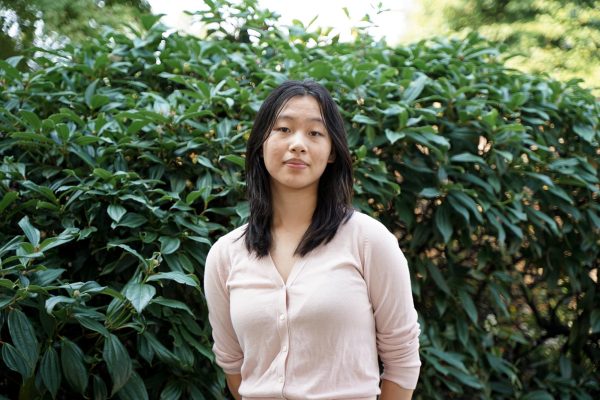

Junior Gigi Grimm (she/her) is a member of the Yakima tribe and both of her parents have Native American heritage. She said the perception of Native Americans in school is inaccurate.

“I got really upset when we learned about Native Americans or Indians. And like, all of the information is wrong,” Grimm said. “Especially when we were younger and Christopher Columbus came over and it’s like, oh, they all had Thanksgiving together. That really angered me — it was just so wrong. I always kept hearing such a good, fantasized, beautiful version of the story that was a horrible massacre.”

Junior Isabella Mejia (she/her) is part of the Choctaw tribe in Oklahoma and also said the representation of Native Americans in her history books is inaccurate.

“I feel like there’s so much more than just the major tribes like Cherokee, Navajo and some of the other ones — there’s so much more and so much differences within cultures between each tribe, but yet, we’re all grouped together as like, ‘oh, you’re Native American,’ or ‘you’re Indian’ or something that’s just a little bit more basic, and we don’t go into depth about different kinds of Native American tribes and their specific parts of their culture that actually make them who they are,” Mejia said.

Mejia said her history class recently discussed stereotypes and perceptions of Native Americans, which involved how Native Americans aren’t taken seriously.

“We were talking about how Native Americans are seen as something that you can almost play around with,” Mejia said. “It’s not the right word, but people play dress up as westerns, cowboys and Indians. And even like, I used to go to private school, and we used to have Indians versus cowboy dress up days and stuff like that, but in reality there’s so much more to just Indians and cowboys, right?”

Grimm said that although people have acknowledged the atrocities done to Native Americans, not much is being done about it.

“It’s just like a cartoon show, like you know in movies or shows when Native Americans are shown, they’re in a little teepee [with] their spears, their moccasins, headdresses,” Grimm said. “It’s just very commercialized, the way that it’s showcased and I feel like people think Native Americans are just people that live in teepees and big groups outside, which is kind of true, but there’s also a lot more to it.”

Mejia and Grimm both expressed a desire to understand more about their Native American heritage. Grimm said her great grandma was mistreated because of her Native American ancestry, and as a result, her great grandma prevented her family from learning about the culture for a long time. Grimm said the history curriculum doesn’t dig deep and show how Native Americans were affected — just what happened to them.

“I know my great grandma, she used to get rocks thrown at her walking to school from the white boys because she was super dark. So then she didn’t involve her children in the tribe until they got older. So then my mom and I weren’t super involved with it,” Grimm said.

Generational trauma refers to the economic, cultural and psychological effects of a traumatic event that are felt across generations, even after the event has passed. Evans said he experiences the consequences of generational trauma.

“I may not have suffered any of those things — going to the boarding home or being forced to live on the reservation — but my grandparents, my great grandparents might have, and I’m still feeling the effects as if I was living on the reservation and being persecuted,” Evans said.

Many stereotypical symbols of Native American culture — such as totem poles and teepees — do not originate from the Puget Sound area. Evans said the internet is riddled with misinformation about Native Americans, and that it’s hard to tell what’s true.

“Get in the canoe and paddle, become involved with the cultural things. But be aware that it is not the same as it used to be. And if you want to know what it used to be, you need to go look, see for yourself,” Evans said.

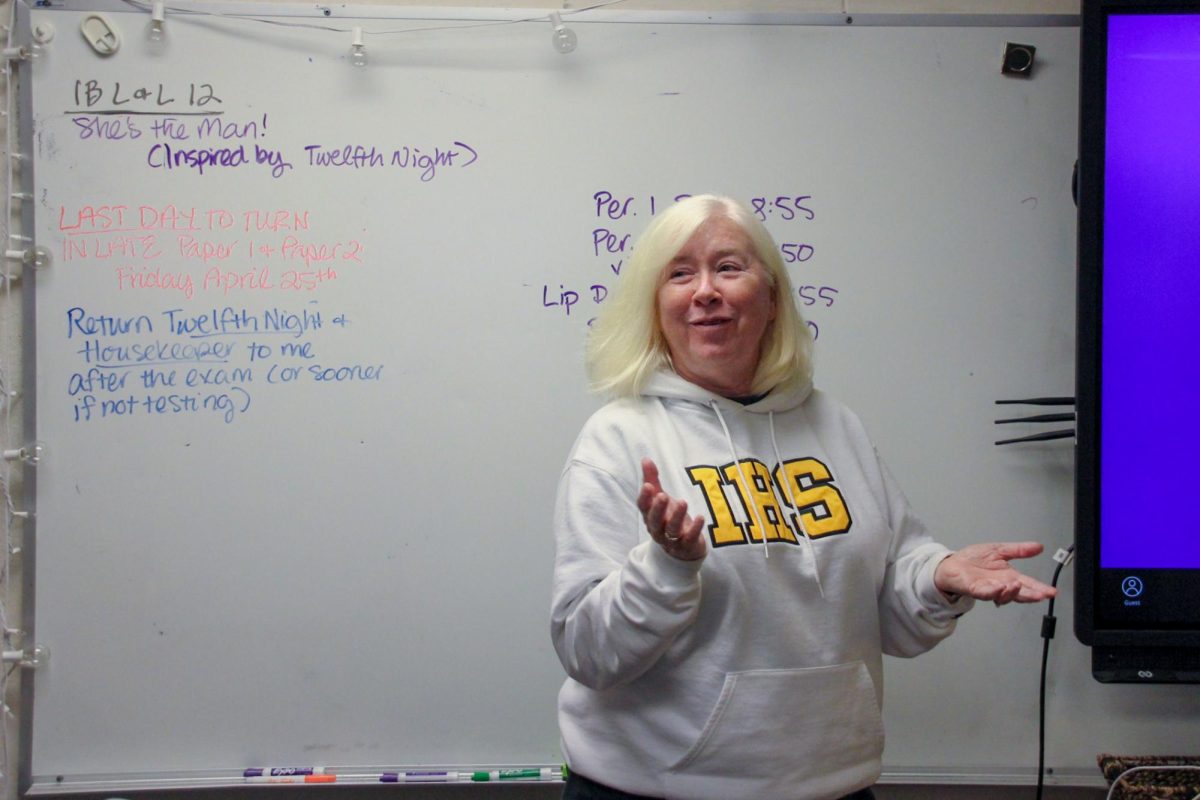

Pre-IB History 9/10 and AP U.S. History teacher Luke Derror (he/him) said the biggest challenge to covering Native American history in class is the lack of time. He said the first few years he taught world history, several students said the curriculum was too Eurocentric, and eventually the history department switched to its current curriculum, which is based on readings from the World History Project.

“If there are students feeling like ‘Ah, I want to talk more about Native Americans,’ then I think they should voice that,” Derror said. “Their self-advocacy can change the curriculum.”

Native Americans make up around 1% of students at Inglemoor. From the Choctaw Tribe in Oklahoma to the Yakima Tribe in southwestern Washington, each one carries a diverse and intricate background. Mejia, who is 1/16 Choctaw, said her great-grandfather crossed the Trail of Tears, a forced relocation of Native Americans by the U.S. government from their homeland to reservations.

“My favorite part about visiting our tribe is the history that we have behind it,” Mejia said.

Mejia said her family tries to visit her tribe in Oklahoma every year, but their busy schedules make it difficult. When they go to Oklahoma, she said they always visit museums and the land her great-grandparents built a farm on.

“I have so much more behind me,” Mejia said. “My family members have gone through so much; and the fact that it’s still stayed in my family, it’s absolutely amazing that I still know a lot more of my heritage than a lot of other people who say that they’re Native American don’t.”

Grimm, who is 1/4 Yakima, also said she’s proud of her background. She said that her whole family has been very connected to their heritage.

“I think Native Americans themselves, their morals are really important,” Grimm said. “Like when they would kill an animal, they use every single part of it; they don’t waste anything. Whatever they do, they do to survive, not to be greedy.”

To connect with her family’s culture, Mejia attends powwows and other events.

“Every year, whenever we go down to Oklahoma — which is hard for my family because we’re always really busy and live so far away — we try to participate in powwows,” Mejia said. “We’ve got to attend some at Monroe High School, and we’ve tried to attend some that are affiliated with Northshore. Basically, we just celebrate and dance and generally, there’s some sort of topic. Sometimes it would be appreciating nature or respecting a god or something like that. Celebrating harvest is one of the biggest ones because Native Americans and our culture are so dependent on land.”

NSD offers a Native American education program that not only provides culturally relevant activities, programs and opportunities but also educational support and mentoring. It assists Native American students during the school year through services such as mentoring, homework support, cultural events and job shadowing. Mejia said she thinks this program is very important since Native Americans are a minority that struggles more academically because of poverty.

“I personally don’t really see much of an impact academically, but I do know that [in] schools within especially Oklahoma, Native Americans struggle academically because of the lack of resources, and I think that’s something that does need to be more addressed,” Mejia said. “But I think it needs to be expanded to other Native American cultures within the United States and not just within highly densely populated Native American cultures.”

Senior Luke Geronimo (he/him), a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation in Oklahoma, said that while he’s never been to the reservation in Oklahoma, he has attended powwows and meetings.

“We don’t live on the reservation, and we don’t have a clear connection,” Geronimo said. “But being with family and being around the people that you love and care about is one of the big takeaways from our roots.”

Grimm said when visiting the reservation, she noticed the impacts of the treaties that still affect her tribe to this day.

“We should first give Native Americans credit for all that they went through and all the atrocities that were committed on their land and to them,” Geronimo said.