In the past twenty years, the southwestern region of the U.S. has been experiencing extreme drought. As a result, the Colorado River’s flow is severely depleting, causing over 40 million citizens to experience water scarcity. The debate surrounding the river’s water distribution began in the 1920s and has continued since. Since climate change has intensified the drought, negotiations about federal laws, treaties with Indigenous tribes and how to divide the river’s water amongst states have escalated.

In 1922, representatives from seven southwest states — Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming — signed the Colorado River Compact, which determined water allocations for the following century. Although scientists at the time asserted that the region was prone to droughts, legislators ignored the problem to simplify the political task of dividing water rights. Consequently, differing interpretations of the Colorado River Compact continue to haunt Southwestern cities and farms today.

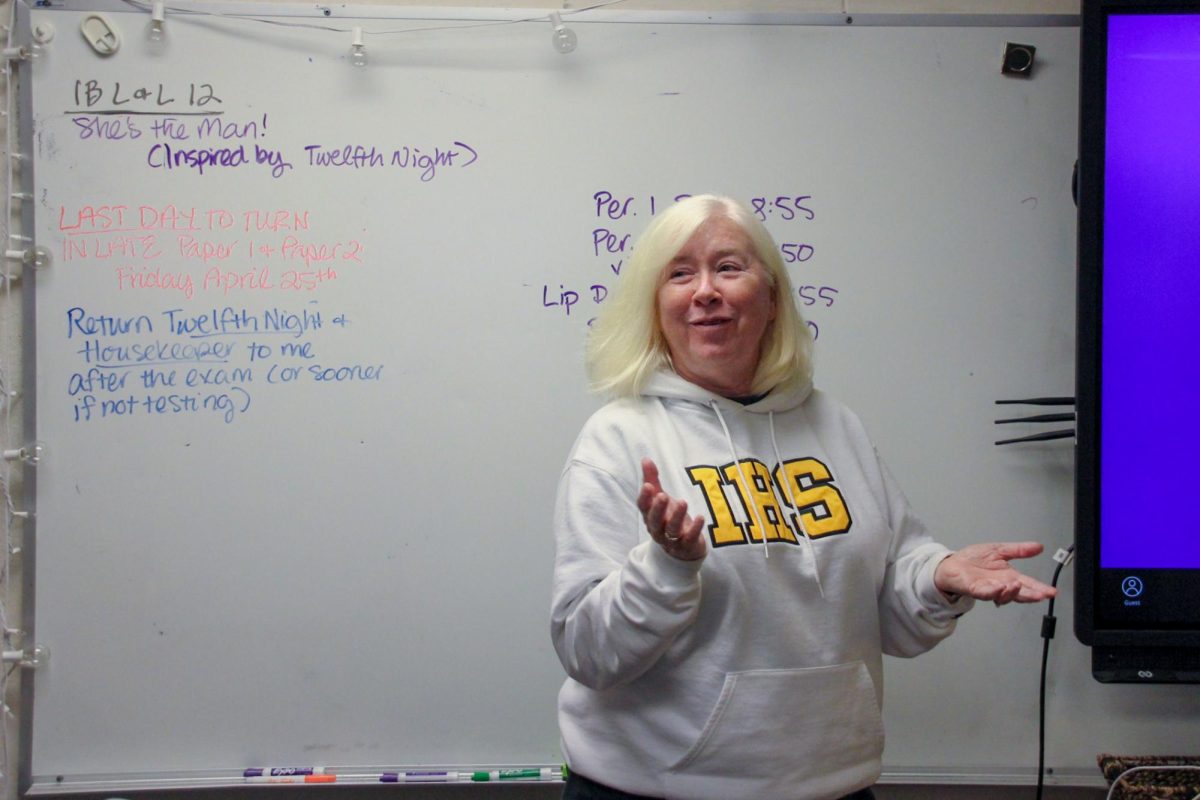

“The Colorado River Basin water supply has been shrinking for a while, and the cities have been dramatically reducing their water use. Water use in these cities is going down even though their populations are rising,” said John Fleck (he/him), professor of Practice in Water Policy and Governance at the University of New Mexico.

The Colorado River supplies water to irrigate crops like lettuce, cabbage, kale and melons. However, most water is used for alfalfa crops. Alfalfa is a plant grown across the country to feed dairy cows. Water scarcity will impact farming communities the most, which could lead to food shortages and endanger economic livelihoods.

“In some places, as much as 90% of water goes to agricultural activity, and a lot of that in the upper parts of the basin — Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah — is pasture for cattle. In the lower part of the basin, it is pretty intensive commercial agriculture. If you go to the market in your town — Bothell, Washington — right now, today, that lettuce will have been grown with Colorado River water in the deserts of Southern Arizona or Southern California,” said Fleck.

Fleck said the real struggle is for communities whose livelihoods depend on agriculture. He said for places like Imperial Valley in California, water scarcity will harm people. He said the tragedy of climate change is that people who have built their lives around agriculture and the type of climate that benefits the crops they are growing will be severely hurt.

Private investors from Wall Street and other large corporations have taken advantage of water scarcity at the expense of rural communities by purchasing the rights to land that contains a water source and waiting for them to become more valuable before eventually selling them. Fleck said that although it’s controversial, investors buying out land with water rights in areas experiencing the southwest drought isn’t a huge issue because investors only purchase a small fraction of the water supply.

“For people in a farm community, owning that land and water is their most valuable asset. So their ability to sell that to the hedge fund or whoever — that’s their retirement savings account, that’s how they can pay for their kids to go to college,” said Fleck. “There was an effort in Colorado a few years back to try to come up with legislation to prevent speculation, and there were a lot of people in the farm communities who objected because it reduced the value of their asset.”

Fleck said that everyone has to share the burden of water scarcity. He said that cities far richer than farm communities should collaborate with farming communities to figure out how to share the water.

“In California, for example, the big water districts for the cities will pay farmers handsomely to fallow some of their lands. Fallowing means just do not irrigate, leave it sitting. That water helps ensure the security of water supplied to the city and provides cash flow to these rural communities,“ said Fleck. “Those kinds of arrangements are really important, and that comes from collaboration.”

According to Fleck, it’s important to accept that communities in dry places must survive with less water. Technical solutions include purifying and reusing city wastewater, desalinating ocean water and improving agricultural efficiency.

Global warming’s impact on ecosystems and human communities is directly felt through changes in water. The Colorado River drought and debate are only a snapshot of a larger picture of climate change’s effects as a whole.

“In general, under climate change, dry places get drier and wet places get wetter. So in some places, you will see bigger floods as a result of climate change and in other cases, you will see reduced river flows. There are a lot of rivers around the world that are in sort of dry climate areas that are seeing or we can expect to see reduced flows,” said Fleck. “There’s a lot of different, complicated problems posed by water change, as a result of climate change. The specifics of what we’re seeing here may be a little different, but in general, we optimize human societies around the available water.”