Defining Teen Dating Violence

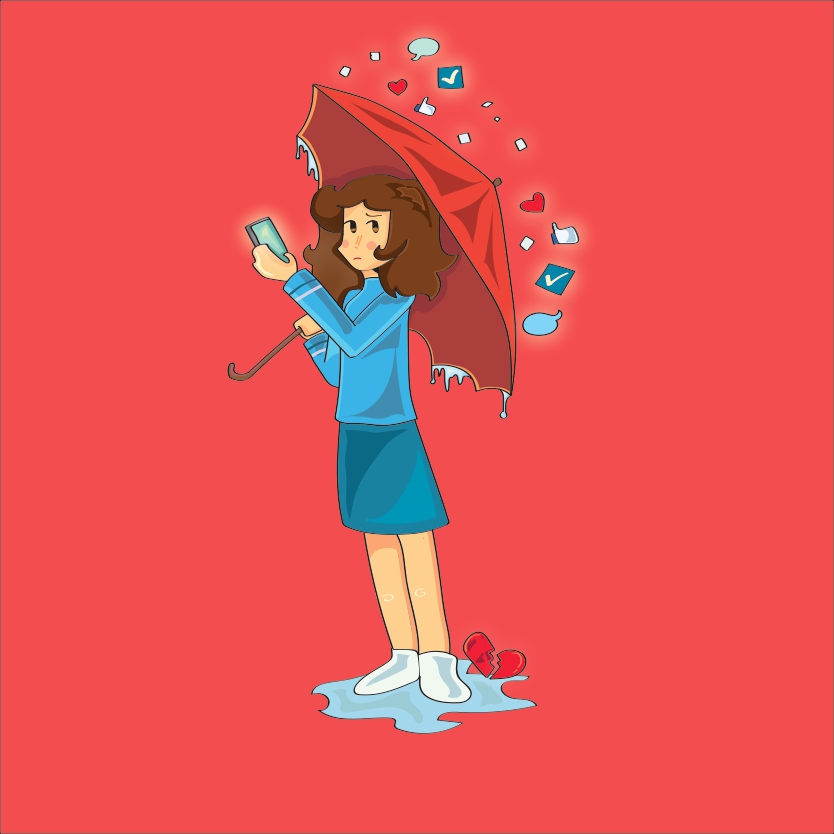

In a recent Nordic News student survey regarding Intimate Partner Violence, also known as Domestic Violence, 14.4% of 94 respondents said they are survivors of emotional domestic abuse in a romantic relationship, and 6.7% are survivors of physical domestic abuse in a romantic relationship. In addition, 54.3% of respondents reported that they have witnessed emotional or physical abuse in a friend’s relationship.

Teen Dating Violence is a form of IPV that specifically refers to abuse in a dating relationship among adolescents. TDV affects almost 1.5 million high school students in the U.S., according to the National Institute of Health.

TDV can be physical, emotional and/or sexual. Not every abusive relationship looks the same, but abusers will usually establish power and control over their victims to perpetuate the abuse. A tool of reference for identifying abuse is the wheel of power and control.

The wheel shows eight emotion-based and continuous tactics, including coercion and threats; intimidation; emotional abuse; isolation; minimization; denial and blame; the use of children; male privilege; and economic abuse.

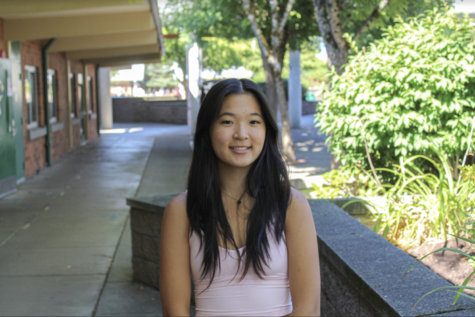

Senior Phoebe Nakamura* (she/her) disclosed that she was in an abusive relationship from the end of her sophomore year until the beginning of this school year.

Nakamura defines emotional abuse as making the victim feel bad about themself; making them question themself; gaslighting them; guilt-tripping and manipulating them; saying things like “If you love me, you’ll do this.”

Nakamura said that her former abusive partner would guilt-trip her in an attempt to control her actions.

“He would make me feel really bad about everything, like, ‘Oh, if you don’t do this, then I’m gonna be miserable,’ that kind of stuff,” said Nakamura. “Just making me feel like a bad person if I don’t do whatever he wants.”

Isolation includes controlling what the victim does, who they see and talk to, where they go, limiting their outside involvement and using jealousy to justify these actions.

Nakamura said that her partner didn’t want her to attend a trip for a summer internship because he didn’t trust some of the other people who were going.

“I kind of missed out on a lot of opportunities because he didn’t let me do it, and he would tell me that ‘it’s for my own good’ and, ‘this is bad for me’,” said Nakamura. “I also cut off a lot of friends because they were ‘bad influences’ or ‘It’s gonna ruin the relationship’.”

Senior Marie Georgio* (they/them) said that they experienced sexual coercion and emotional abuse in relationships they were in during eighth and ninth grade. Georgio said that they believe the only reason their former partner was with them was to have sex with them.

“I didn’t know that at the time because I was so desperate to cling on to someone just because my mental health was pretty down. So I didn’t really have anyone else,” said Georgio.

Georgio said they didn’t realize that this relationship was abusive until later, when they sat down with their parents and confided in them about their experience. They said their former partner would insult them, put them down and threatened to slap them.

It isn’t always easy to tell if someone will become abusive at the beginning of a relationship. Abusers often present themselves as charming, ideal partners at first. Warning signs of domestic violence can develop and intensify over time rather than presenting themselves overnight.

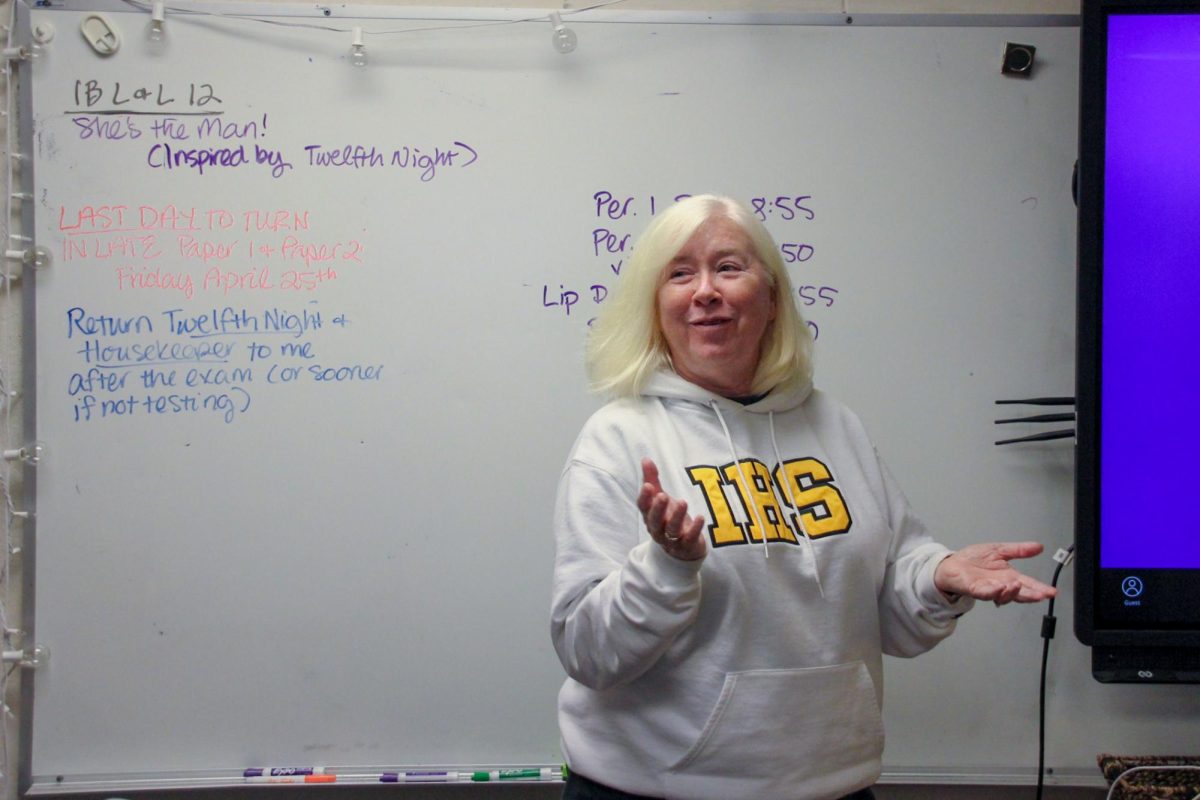

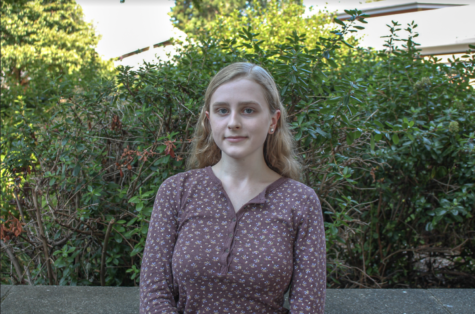

IB English teacher Marita White (she/her) said she experienced intimate partner violence in a previous relationship, during which she was in deep denial of what kind of relationship she was in.

“I kind of wrote it off as like, ‘this person is passionate,’ or, ‘this person just has some anger’,” said White. “And it honestly wasn’t until I met another person who had been in a similar situation, and they showed me the wheel of power and control, that I even understood that there were resources available.”

Nakamura said when she began to notice she was being abused, she would confront her partner about it, and he would deny it.

“Anytime I would try to talk to him about it, he would just shut it down and tell me that I’m the problem,” said Nakamura.

In her abusive relationship, White said that her former partner often minimized or denied the abuse, and shifted the blame to her.

“I would stand up for myself, and I would either be told that I was misremembering the events, or I was the one who actually caused the issue. Even when I had been physically hurt, then it was all of a sudden my fault that I made them do it,” said White.

Taking the next steps

Nakamura said her abusive partner would get upset when she discussed their relationship with others, which is why she initially struggled to reach out for help. Nakamura was able to confide in a few teachers, who gave her support and advice. She said those teachers were amazing, and always checked up on her.

Students should tell a trusted adult if they are experiencing teen dating violence or if they’re in danger. There are teachers and other staff members at school who are privy to information on the next steps that should be taken.

When Nakamura’s former partner stalked her at school after she attempted to break up with him, she said administrators helped her end the relationship and took disciplinary action against him. Administration also sent Nakamura to see her counselor, which she said helped.

Counselor Jennifer Orhuozee (she/her), who serves students with last names starting from A to Dora, said that, if a student comes in and discloses information about a relationship that sounds emotionally abusive, the procedure is to refer them to counseling, either outside counseling or with the school’s mental health therapist. Counselors have the ability to alter schedules if a student doesn’t feel safe in a classroom with a specific individual.

The counselors aim to create a safe place for students to talk about strategies and what to do next.

“I always encourage them to talk to someone in their lives — an adult — whether it’s family or someone they are close to,” said Orhuozee.

But Orhuozee said that, when it comes to physical abuse, the line becomes a bit murkier and trickier. She said counselors have to distinguish if the alleged physical abuse is something that should be reported to the authorities.

“I encourage students to come and talk. It depends on what’s going on, and it also depends how much they reveal,” said Orhuozee.

In her IB Language and Literature 11th grade classes, White introduces identification and evaluation tools like the wheel of power and control. Her class examines bodies of work such as poetry and film that discuss IPV. White said this aims to help students piece together and identify potential red flags in relationships.

Nakamura said there should be more mental health resources and information on healthy relationships available for students.

“I feel like we should be able to stop that behavior before it happens,” said Nakamura.

For teenagers, the biggest example of relationships is that of their parents or guardians, who hold some responsibility to teach their children what a healthy relationship should look like.

“I think that we need to have more nuanced conversations with our kids about different types of abuse, like reactive or financial or sexual. Abuse is not just hitting somebody,” said White.

Senior Trevor Berry (he/him) said his parents taught him about healthy relationships through example. Berry is currently in a relationship that he describes as healthy. He said that he and his girlfriend share trust, good communication and similar boundaries.

“I have heard about a lot of other relationships where their [significant] other can’t go out with their friends, or people of the other gender because they’re worried something’s gonna happen, but I just don’t have that fear because I trust her,” said Berry.

It’s important for teenagers in relationships to establish a strong friend group outside of their romantic partner. Establishing boundaries and balancing friendships with romantic relationships will make it less likely for teenagers to fall in the trap of being a victim.

White said that, if an intimate partner is pushing back on boundaries, examining those boundaries can be helpful to decide whether or not they have a reasonable request.

“Is your boundary that you spend Saturday night with your friends and this romantic partner is worried about that? Maybe include them to come out with your friends. Maybe reach a compromise. But if your romantic partner is upset with you or hurting you when you don’t answer the phone every time, that’s an unreasonable request, and I think deep down, we often know what’s reasonable and unreasonable,” said White.

White added that it can be difficult to assess boundaries when a victim has lost their sense of reality after repeated gaslighting and minimization of their abuse. She said having a conversation with a trusted friend can help the concerned partner determine if a boundary is reasonable or not.

White said that while arguments are normal, name calling and putting hands on someone else is not okay. She added that “I feel” statements are helpful because they take the blame off your partner during an argument and don’t dismiss how they may feel.

Berry said that, in his relationship, he and his partner take time to cool down after an argument before reconciling.

“Normally, it takes a minute. We’ll just both be a little angry for a bit but then we always call each other back and then just talk about it in a calm tone of voice without aggression or anything, and just realize that we’re on the same side.”

Leaving the Relationship

It’s often difficult for someone to recognize that they’re being abused. Because of the control abusers have over their partners, they’re able to manipulate victims into believing that their mistreatment is normal or even justified. A teenager’s abusive partner may attend school with them, which can further complicate the process of leaving.

“I can imagine in high school, it’s also a lot more complicated because there are other friendships involved,” said White. “Like you might be dating someone who is in your friend group, and so it might feel like standing up for yourself is also like losing part of your support system.”

Because some abuse victims struggle to identify themselves as such, convincing someone to leave an abusive relationship can be challenging. Abuse is a cycle that breaks victims down over time, and it’s difficult for victims to reject this cycle because it becomes familiar and normalized to them.

The cycle, also known as the cycle of violence, is a well-known theory developed by Dr. Lenore Walker, an American psychologist. It’s characterized by four phases: tension building, the incident of abuse, reconciliation and calm. Behavior exhibited by the abuser in the reconciliation and calm phases is key in getting the victim to remain in the relationship.

During the reconciliation, or “honeymoon” phase, the person who committed the abuse will attempt to set things right again after an abusive incident by offering gifts and behaving extremely affectionately toward the victim.

“You can’t really trust anything that this person is saying to you because everything they’re saying is just to keep control over you. Even if they’re being super sweet at times, it can be used against you,” said Nakamura.

The honeymoon phase can also happen when the victim tries to leave. Nakamura said that when she’d try to leave, her former partner would act as if he’d changed to win her back before reverting back to his former self.

“He would say all this stuff that made me feel really happy for him and made me truly believe that he had changed. And he was like that for about five days. And then pretty much right after I said I’d be his girlfriend again, he went back to the same thing,” said Nakamura.

The “calm” phase follows the reconciliation phase. This is when explanations and justifications are made to the victim to help them excuse the abuse. In most cases, the abuser shows remorse and promises to change or accept their partner’s boundaries. Victims leave this phase believing that the incident wasn’t that bad, or that it’s a thing of the past.

Nakamura said that the second time she got back together with her abusive ex, he promised to respect her boundaries.

“But it didn’t happen like that. The first few days we hung out, he was super respectful, super patient, exactly the way he said he would be, and then later, once he kind of sucked me back in, he started bringing back those habits. And then I realized, ‘Okay, yeah, that was a mistake’.”

Although the cycle of abuse described is widely used by professionals, it’s important to acknowledge that cases of intimate partner violence vary from relationship to relationship, and not all abuse may happen in a cycle.

White said that there’s a lot of misconceptions about why people who have been abused stay in those relationships, and that it’s important to be careful in approaching friends who may be experiencing teen dating violence.

“They are very likely to deny it or become defensive because that’s what they are doing for themselves,” said White. “And so I think the best way first to maybe approach it is just to get close with that person and really let them know that you’re a safe person to confide in.”

White said that if a student notices signs of abuse from a friend, or if a friend confides that they are in an abusive relationship, the student should absolutely have a conversation with them.

“I would do everything you could as a person that they trust to express that that is not normal, because that will help your friend understand that this is an abusive situation that they need to get out of,” said White.

White said it’s important not to give up on that friend, but sometimes it doesn’t help to constantly tell a friend that they need to leave the relationship, because they may be unable to leave for a variety of complex reasons. Instead, White emphasizes that it’s important to be a good listener and echo back questions to help them reach their own conclusions.

White’s advice falls in line with Dr. Shawn M. Burn’s recommendations in her book Unhealthy Helping.

Establishing a strong support system is crucial for victims who are attempting to leave their abusive relationships. Support systems ensure that the victims have friends and family they can fall back on and can prevent them from returning to their abuser.

“Someone might not want to break up with that person because that’s the only person they really have, and they feel like no one’s gonna be there for them when they do leave,” said Nakamura.

White stressed the importance of starting the conversation about TDV among students to eliminate the taboo surrounding the topic.

“Once you read this article, go check in on your friends and just say, ‘How are you doing?’ ‘Have you seen any of this?’ ‘Have you experienced any of this?’” she said.