Masculine expectations erode mental health

This article contains discussion of suicide. If you are uncomfortable reading about this topic, we advise that you skip this section.

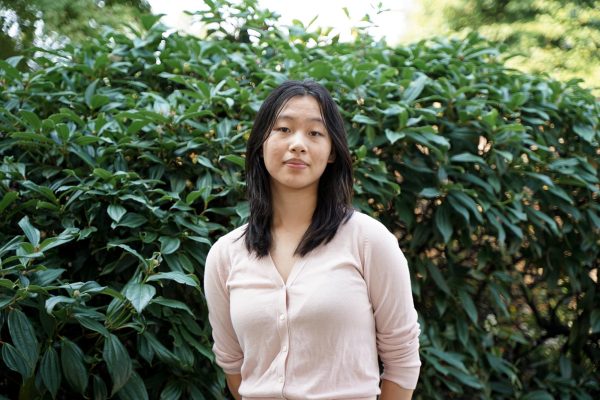

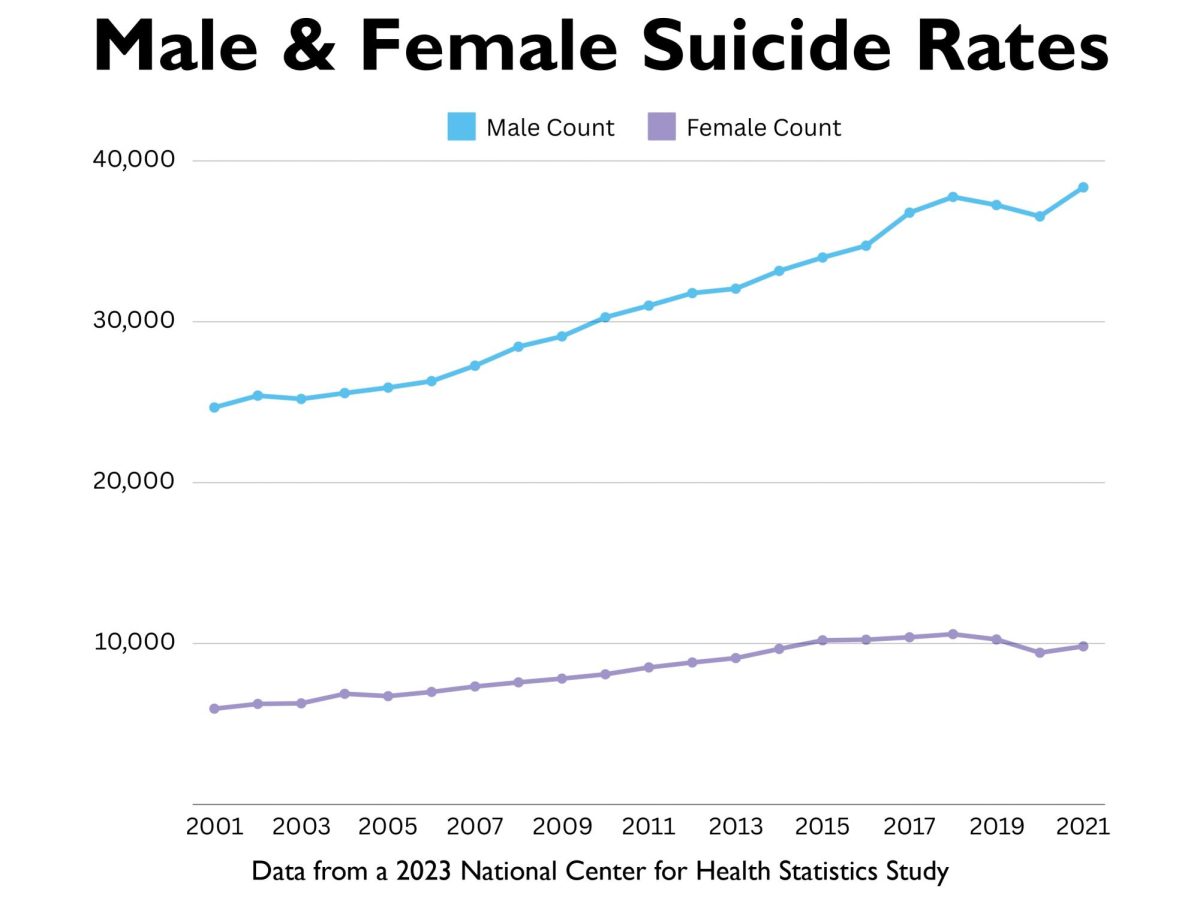

Men are more likely to die by suicide than women. According to the CDC, men account for nearly 80% of all suicides in the United States. Although both men and women are affected by mental illness, it is often overlooked in men, in part because statistically, men are less likely to seek help for mental health issues than women; in a survey conducted by the American Psychological Association, only 35% of men reported that they would seek help from a mental health professional, compared to 58% of women. Senior Gavin Krambrink (he/him) said that mental health issues are a very private subject among men.

“There’s very little willingness to talk about it,” Krambrink said. “I think for most people, it takes a lot for you to talk to someone, to be comfortable enough to talk with them about it. You always hear growing up things like ‘Guys got to deal with it,’ so you’re not supposed to talk about it because you’re a guy.”

Senior Jeremiah Lundberg (he/him) expressed similar opinions, saying that societal expectations impact his desire to talk about his issues.

“Whenever I’m kind of struggling with something, going and talking to someone about it is never my first option, just because I don’t want to be that person that’s whining about stuff all the time,” Lundberg said. “It’s definitely not as common to see guys open up about having actual struggles. They’re definitely a lot more guarded with that, probably because they feel like they’re showing weakness.”

Toxic masculinity — an exaggeration of traditional masculine stereotypes that glorifies aggression, dominance and violence — presents a major blockade in men’s mental health. Phrases like “man up” or “boys don’t cry” only exacerbate the problem. Toxic masculinity is also deeply ingrained into sports culture. As one of the captains of the varsity football team, Krambrink said that toxic masculinity has always played a part in his sports career.

“Even at junior football, I was taught to never cry or put your hands on your knees or bend over in any way looking tired, or else you’ll get yelled at and have to run for it,” Krambrink said.

Krambrink said that seeing men’s emotions borders on the line between unnatural and uncomfortable. During football, Krambrink said that coaches are available for help, yet no one will talk to a coach; instead, they try to ignore it.

“You’re like, ‘Hey, bro, that was tough,’ but you gotta just flush it and not think about it anymore,” Krambrink said. “The whole point is, you mess up once, and you just have to forget about it and do better.”

Senior Julius Sidow (he/him) said that societal pressures are partly what makes talking about male mental health so difficult.

“You can be perceived as being weak, which means you don’t want to express yourself because you’ll get embarrassed because of it. These pressures almost force you to conform to society’s structure of how they perceive other men,” Sidow said. “It’s like the bystander effect. If you see somebody getting made fun of because they’re trying to show their emotions, obviously you don’t want to be that person. So expressing yourself makes you feel like you’re a lesser person sometimes, even though reaching out to other people — maybe a counselor or a therapist — is the strongest thing that you can do.”

Lundberg said that steps have already been made to move away from the idea of being perceived as weak. Similarly, Sidow said the barriers around mental health have improved, especially among friends.

“I think a lot of men still aren’t able to talk about it, but I have noticed that having really good friends that know how to openly share their emotions, and some of them, they can encourage you to do so as well,” Sidow said. “I think also, just with maturity, people understand that it’s a serious topic and that you need to talk about it and understand it.”

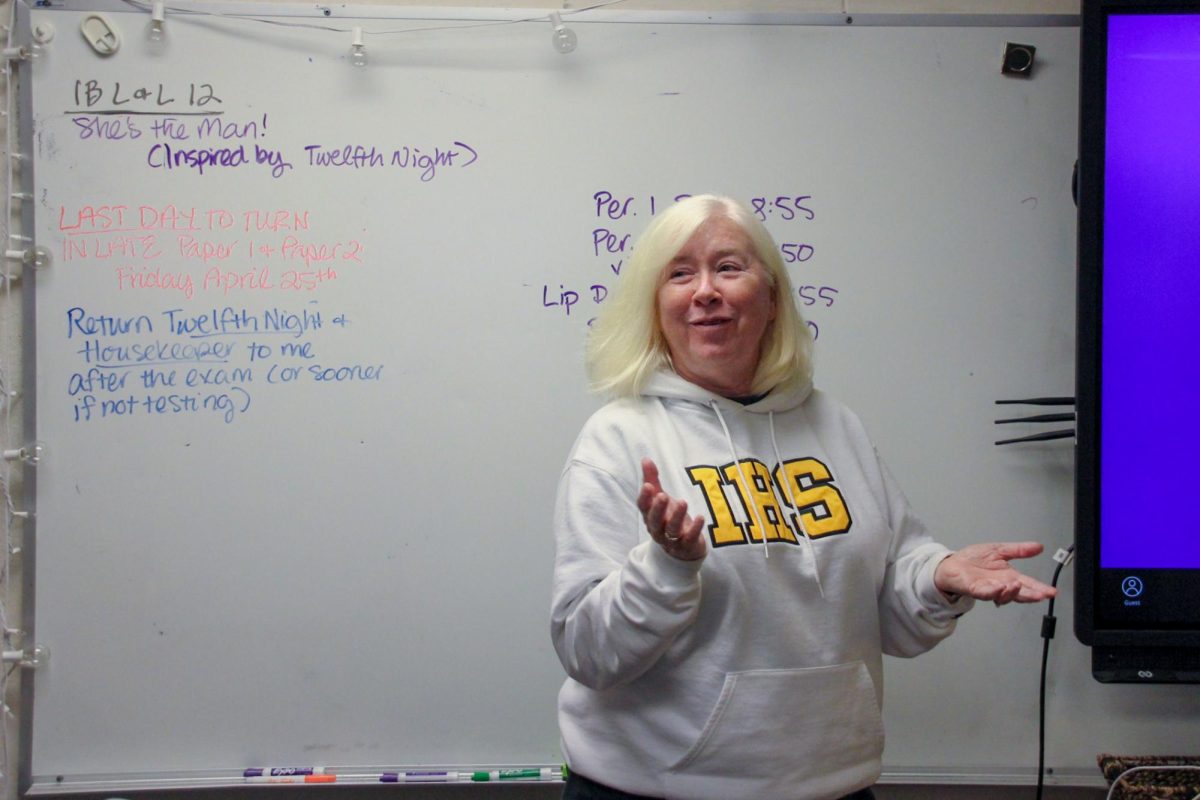

The Manosphere is an online community populated by podcasters and influencers like Andrew Tate and Joe Rogan who promote hyper-masculine and misogynistic ideas to their largely male following. Former gender studies teacher Brittney Kim (she/her) said that internet communities can be a powerful influence on boys who are navigating their teenage years.

“Adolescence is a really tough age,” Kim said. “It’s when kids figure out who they are, and when you have someone giving them an answer and giving them someone to hate, that’s very powerful fuel, because kids have a lot of frustrations.”

Kim said she’s had students who watch male influencers like Andrew Tate and mimic rhetoric from his show. Every year in gender studies, Kim discussed a court case about sexual assault in schools. Most years, she said, the boys in her class laughed while the girls felt uncomfortable and shared personal experiences about being harassed in school.

“I don’t know about you, but anytime I’m mean, I don’t feel good about it,” Kim said. “It eats away at you. So you can imagine, if somebody is being told their whole life that they need to be aggressive, be violent, dominant, it eats away at them, kind of erodes their empathy.”

Kim said that toxic masculinity encourages violence in young boys, and that violence is either directed inwards — resulting in high suicide and self harm rates — or outwards — resulting in high domestic violence and assault rates.

“It kind of just makes you sad and angry, especially if you’re watching videos and you’ve got some person that you’re following online. Do they really care what’s best for you, or are they just trying to make money?” Kim said.

Senior Payton Hathaway (she/her) said the men in her life, especially her father, brother and boyfriend, rarely cry.

“If I was around a big group of my guy friends, I would never ever, ever, ever want to cry around them, because I feel that if I’m with them, then I need to uphold to those men’s stereotypes, and I need to be not as emotional,” Hathaway said. “But when I’m with girls, I feel that I can say everything that I need to say, and I can be emotional, and everybody else is just going to be emotional with me, because it’s that difference in stereotypes.”

On the other hand, biology teacher and former football assistant coach Christian Hanna (he/him) said that these stereotypes have not affected him. He credits the environment he grew up in as the reason.

“I cry a lot, and I still do. There are some movies that get me every time, man,” Hanna said. “I never was taught to hide emotions or anything like that. I was never raised in such a way that there are particular roles. There were things that I was interested in and that I liked, and my parents encouraged me to pursue the things that I was interested in that I liked, and so I did.”

While he has struggled with asking for help before, he attributes that to his introverted personality rather than gender-based expectations.

“Asking that other person for help gets you the help that you need, and the outcome is far more important than saving any kind of pride or embarrassment, because all those things are temporary anyway,” Hanna said. “I’ve been in therapy, I’ve had counselors and the outcome was the most important thing.”

In his experience, Hanna said, he has not encountered many male figures who push traditional stereotypes onto others. He said he hopes they are a minority of men.

“I think the more everyone experiences and makes asking for help a normal thing, more normalized,” Hanna said. “A lot of people know more things than you do, so why don’t you go ask them?”

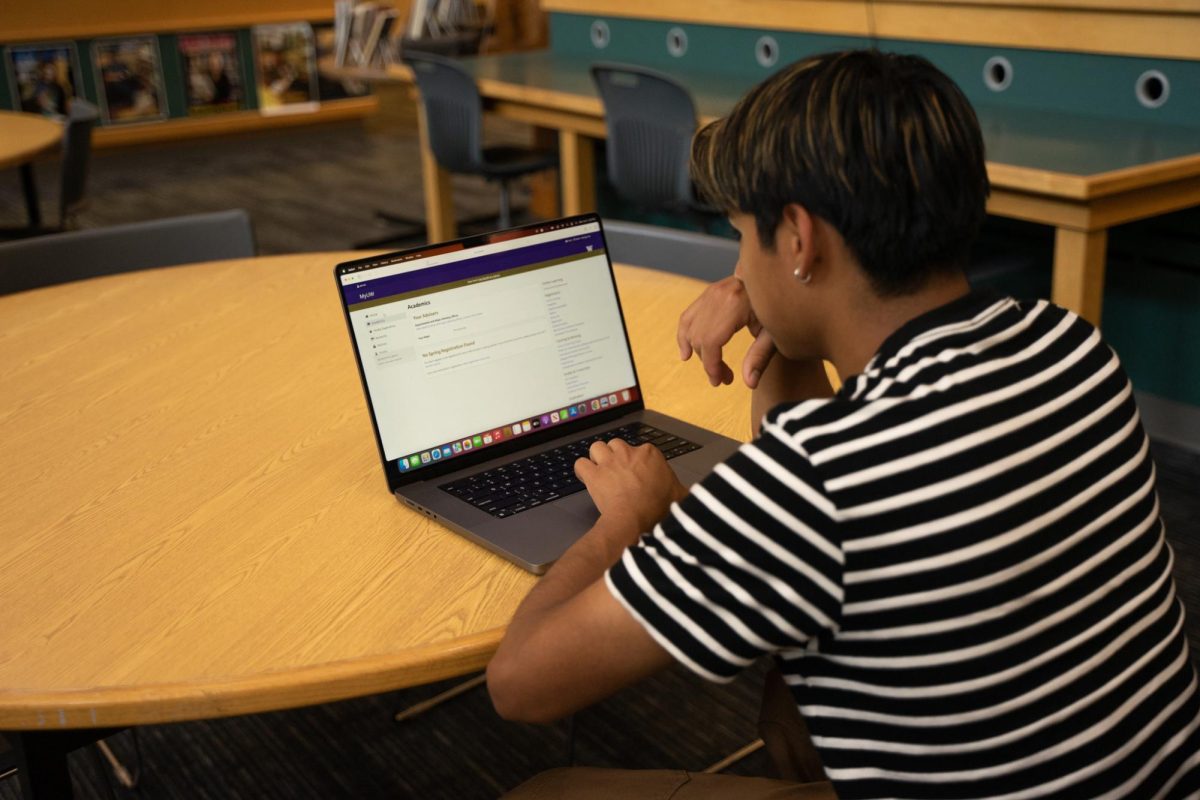

Masculinity and the standards for it vary across cultures, through media, families, perceptions and stigmas. For example, senior Andrew Shi (he/him) spent the first years of his life in China, where he said expectations of men dramatically differ from the expectations in Western society.

“When you imagine masculinity here, it’s more abrasive, or they want you to be firm and confident. That’s not really the case like that (in China). Yes, those are good qualities you have, but the team, the system, or the society, or the school or your parents don’t really value that,” Shi said. “In fact, they want you to be more obedient and hardworking and not shy, per se. It’s called ‘ting hua.’ They want you to be like a good kid.”

Shi not only mentioned the difficult standards he’s seen, but also that it’s difficult for him to open up about his mental health due to Chinese societal pressure.

“I don’t like to talk or open up about my mental health to other people,” Shi said. “To be fair, I can’t particularly point out any specific aspect of society that caused me to be that way; it’s very subconscious. It’s very hard to pinpoint exactly what is causing it. I think it’s just a lot of underlying issues with the expectations.”

According to a study conducted by the UCLA Health Department, Asian American families are 50% less likely to seek mental health services as opposed to other races. In addition, in a study by the Yale School of Medicine, Asian American men are more likely to have depressive symptoms because of the cultural expectation to not talk about their emotions.

“I think especially during middle school, elementary school, I did feel the pressure to not talk about it, just because of the environment that I grew up in. Because at that time I was fresh off the boat, I just came here from China. And mental health is something that’s not really discussed in East Asia,” Shi said.

Similarly, junior Kevin Phan (he/him) said he also feels the pressure to dismiss certain emotions in his Vietnamese culture.

“Just being in an Asian household, you’re often taught to put your family’s needs above your own most of the time. So it’s not always about what you want to say. It’s about what your family needs,” Phan said.

Phan also said a common stereotype he faces is that men should know how to fix everything.

“Whenever my dad’s out of town, I’m always pushed to man up around the house. Another example would be always being super tough and strong, being able to carry heavy things and being able to carry a lot more physically and emotionally,” Phan said. “And I think that emotional side often gets overlooked.”

In a paper published by the Department of Reproductive Health, psychologists reported that the way parents and other family members communicate with their children influences the way they cope with their emotions, especially in their early adolescence around 10-14 years of age. Many men avoid coping with their emotions by not talking about them, or by minimizing the situation.

However, sophomore Allan Gutierrez (he/him), who is Hispanic, said that his father makes sure to check on him frequently.

“My dad is always checking in on me, always making sure I’m fine, that I’m never depressed, just making sure I’m okay everyday.” Gutierrez said this makes him feel really loved.

Cultural expectations not only are passed through families, but through the media as well. Shi touched on what the media is like in China.

“A couple years back (in 2021), China banned any feminine image of men on television,” Shi said. “So basically, they see the Korean boy band type of aesthetic, status band. And you’re not allowed to have those because, I forgot what they said exactly, but it was something along the lines of not promoting healthy masculinity, and demasculinating our youth.”

Junior Aryan Velu (he/him) is Indian, and he said a combination of familial expectations and the media influences a man’s perception of masculinity.

“In the media specifically, Indian men are expected to be really strong and stuff like that,” Velu said. “As I said before, they’re also meant to be really successful. And I feel like if they don’t live up to those expectations, they can become really depressed. And that just really affects a whole family in general.”

Velu said that in Indian families, getting into a really good college is akin to the epitome of success.

“There’s also a lot of emphasis on getting a really high paying job,” Velu said. “And I feel if you don’t reach that status, it messes up your mental health in a way, especially because of the familial expectations that are placed on you.”

Overall, the standards imposed onto men by their families, society and culture is something Velu wants to see change in.

“I want more men to express themselves, express their full needs, what’s going on, if they’re stressed out or what problems they’re having, because they tend to hide themselves, especially in Indian culture, due to those cultural expectations,” Velu said.

Talking more about male mental health and giving men a space to talk is one way to solve the problem, Shi said.

“I think once you hear enough of other people saying it’s okay to talk about mental health, I think a lot of men will start talking about it,” Shi said. “I mean, the reason a lot of men don’t talk about it is just because ever since they were a kid, they’ve been told that you shouldn’t do that. And I think you can do that. You can revert that by just saying the opposite thing.”

Gutierrez makes sure to talk to people when he realizes that he’s struggling.

“Having someone to talk to always makes me feel better, makes me (feel) more cared about, more loved, more supported,” Gutierrez said. “Sharing my emotions to someone I can trust always helps me out, and makes me push through things, and keep moving and pushing on in life.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, these resources are available to help:

– Teen Link: A helpline for teens, by teens 866-833-6546

– King County 24 Hour Crisis Line: 206-462-3222

– 988 Lifeline Chat and Text: Dial 988 for support