On the day of his inauguration, President Donald Trump and his administration signed a series of new policies and reversals to completely rework the U.S. domestic immigration policy.

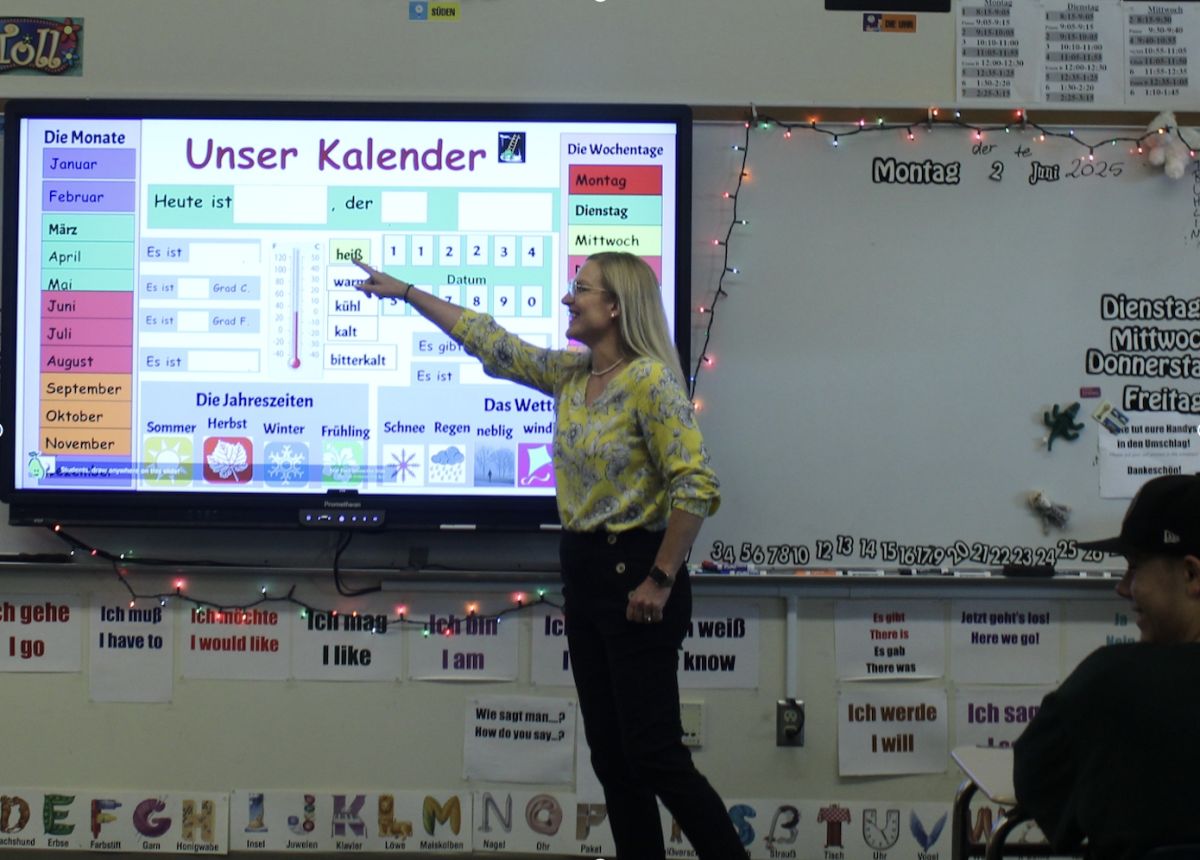

One such reversal came in the form of an announcement from the Department of Homeland Security, which eliminated the Biden-era protected areas policy. Under the new administration, immigration enforcement officials can now enter formerly protected areas — such as schools, places of religious congregation and hospitals — as long as they employ, as the order itself puts it, “common sense.”

In response to this new policy, the Washington Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction issued a news release that outlined how Washington public K-12 should respond.

“The reason we had to put a warning out to districts and kind of caution them is we’ve had more than a 10-year precedent where ICE has said, by matter of practice, we won’t use hospitals, churches and schools,” Washington Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal (he/him) said. “Those are supposed to be safe places for people. Trump has said that’s no longer going to be the case. So there’s a chance they’re going to use those facilities now, and we just need to remind our school districts about that risk.”

Within the release, OSPI instructs districts to ask for identification and only allow access to information or areas of campus directly outlined in a warrant. Districts should request to see identification, contact legal counseling and reach out to the superintendent’s office.

“We just reminded them that there are legal steps they have to take that are still consistent with this new concept that ICE may be on our campuses, and mostly just getting (ICE) to slow down and not overreact,” Reykdal said. “Just because the President signs an order doesn’t mean all of our due process goes out the window. We want to follow the law, but there’s some steps they need to take.”

The Trump administration has also expanded expedited removal, which can now be exercised anywhere in the U.S. and applied to any immigrant who is unable to prove they have resided in the U.S. for at least two years. Washington Governor Bob Ferguson established a “rapid response team” to support families who may face separation due to these new policies. Expedited removal is the process in which an undocumented individual is apprehended and deported before appearing before a judge.

“There are things that can just automatically disqualify you from almost any kind of relief, meaning, from any kind of avenue to get legalized, get your documents and become a resident and then eventually become a citizen down the line,” Seattle-based immigration and civil attorney Magdalena Mendoza (she/her) said. “An expedited removal, the way that I explain it in layman’s terms is it’s basically a permanent way to get you on a blacklist.”

The new expansions on the policy have increased the likelihood of expedited removal applying to an undocumented immigrant, Mendoza said. The policy may also allow ICE officials to revoke humanitarian parole, which applies to individuals who can prove there is an immediate and clear threat of violence or death in their country. It is usually applied for a limited period of time where asylum is ongoing.

Another executive order signed by President Trump threatens to withhold federal funding from “sanctuary jurisdictions,” defined as jurisdictions that “willfully violate Federal law in an attempt to shield aliens from removal from the United States.” It argues that sanctuary jurisdictions harm immigration enforcement efforts.

Both Seattle and NSD have “don’t ask” policies, where they don’t take any information about students’ or residents’ immigration status. Under the new Trump administration, these could be considered “sanctuary policies,” meaning NSD, Seattle or Washington’s federal funding could be at risk.

NSD’s superintendent, Michael Tolley (he/him), said that the majority of the district’s funding comes from local or statewide sources, not the federal government. However, if federal funding was withheld, it would impact certain school services.

Over 70% of NSD’s funding comes from local levies and the state, Tolley said. However, programs like the Individuals With Disabilities Act, which funds special education and IEP programs, and Title One, which provides financial assistance like free and reduced lunches, are funded at a much higher percentage by the federal government.

“We have schools in the district where there is a higher percentage of students who fall within that category — those are the schools that receive Title One dollars. Title One dollars go away, then we no longer have those as a resource to support those students,” Tolley said. NSD also receives funding for students with disabilities or learning differences through the Individuals with Disabilities Act. NSD’s special education program is already underfunded by about $20 million.

Another major move in changing the U.S.’s immigration policy came on Jan. 20, when President Trump issued Executive Order 14160. This order attempts to end birthright citizenship within the U.S. It is one of the most challenged executive orders Trump has signed, as it is in direct opposition to the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, which states “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Trump’s executive order states that citizenship should not be given if one’s mother was unlawfully present in the U.S. and one’s father was not a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident at the time of the individual’s birth, or when one’s mother’s presence in the U.S. was lawful but temporary, and one’s father was not a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident at the time of that individual’s birth. The executive order would only affect people born in the U.S. 30 days after the order was given.

At least four courts have seen attempts to block this executive order, including a multi-state lawsuit filed in part by Washington State’s Attorney General Nick Brown. On Jan. 23, federal Judge John Coughenour granted Washington’s motion for a nationwide temporary restraining order on Executive Order 14160. On Feb. 6, Judge Coughenour extended the restraining order indefinitely. This lawsuit, which is still ongoing, argues that the order violates the 14th Amendment and the Immigration and Nationality Act — a 1952 federal law that provides widespread provisions for U.S. immigration law.

Mendoza said that she doesn’t believe President Trump and his legal team will be successful in passing the executive order. While the Trump administration justified the executive order with a statement about how non-citizens and undocumented immigrants are not subject to the sovereignty of U.S. laws and thus do not fill the conditions laid out by the Constitution for birthright citizenship, this statement was incorrect. All immigrants — both undocumented and documented — are subject to U.S. laws. Immigrants are required to pay taxes, are subject to the U.S. military draft and have the same legal rights as U.S. citizens..

“They’re hinging on some words in the Constitution. They’re hinging on a few words; they’re saying undocumented immigrants are not ‘subject to the jurisdiction,’” Mendoza said. “You’re subject to the family laws of the states, you’re still subject to a custody agreement, even if you have papers or not. You’re also able to sue people civilly … immigrants are subject to the jurisdiction and also have to pay taxes.”

Even if the order is blocked and doesn’t go into effect, Reykdal noted that there could still be consequences for students and families in Washington state.

“What if those families have kept those kids out of services for fear that they’ll be detained?” Reykdal said. “Are there kids out there who are in deep financial distress, not getting resources? Are they being denied access to their education? Because no family is going to put their kid in a situation of a family separation. I think it’s very, very real — the impact that’s happening. Even if we don’t see it, because it isn’t an official action yet, the purpose is the fear, and that’s already happening.”